A Cossack from Djibouti: How a Russian con man founded a colony in Africa

Over the past couple of years, Russia has been increasing cooperation with African countries both in the economic and military sectors. This year, Moscow and Khartoum finally made progress on an agreement on constructing a Russian naval base in Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast.

However, Russia’s wish to be more actively involved in the continent dates back over 100 years, to a 19th-century attempt to gain a foothold in the Horn of Africa. The first and last “Russian colony” in Africa was short-lived, resembling an adventure movie much more than a European colonization project. This was hardly surprising, since the colony was not initiated by the Russian state, but by one of the most brilliant con artists of his time.

The Black Sea scam

In 1883, a dubious character appeared in St. Petersburg. Dressed in a Cossack uniform, he made rounds to newspapers, charitable institutions, and government offices. In all these places, he told the same story: he was a representative of the Cossack army which for years made a living hunting and engaging in mercenary activities in the wilds of Anatolia and Kurdistan. His people’s dream was to return to their lost homeland. But to create a new settlement of Cossacks on the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus, they needed funding. The man was a self-proclaimed hero who bravely fought the Turks in 1878 but could not disclose the details, since the matter was top secret.

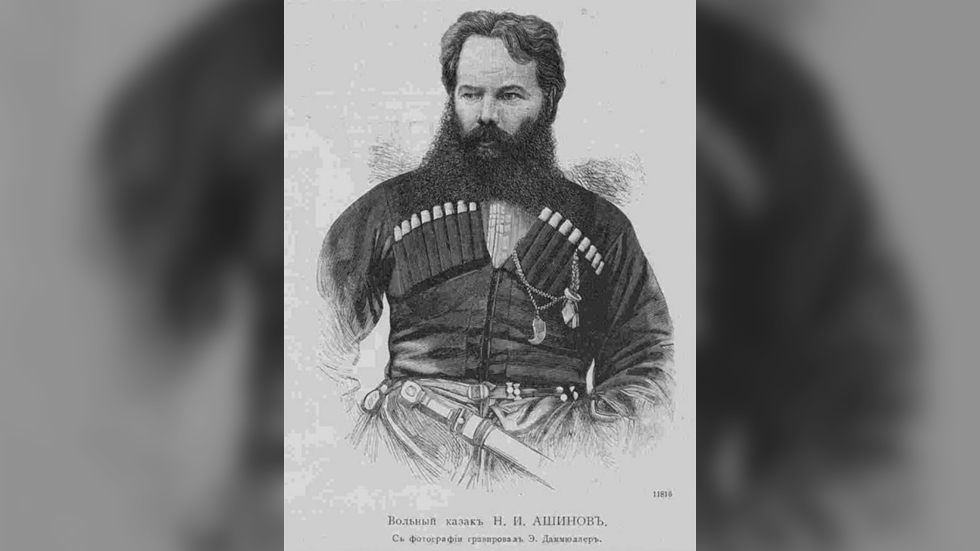

The name of this rhetorician was Nikolai Ashinov. Of course, he wasn’t any kind of war hero. Ashinov was born in Tsaritsyn – a city on the Volga River which in the 20th century became famous under the new name of Stalingrad – and for a long time he was known only as a gang leader in his hometown. The gang was eventually dispersed by the police, but Ashinov retained a flair for commanding people. He had a knack for making friends and once he started lying, he just couldn’t stop.

Ashinov didn’t represent any Cossack army either. He invented the Cossack group in Kurdistan and embellished the fantasy to a grand scale, filling it with detail along the way. He even thought up an elaborate project regarding the relocation of the fictional Cossacks to fertile lands.

After hearing out the brilliant scoundrel, the officials showed him the door one by one. But Ashinov didn’t give up on his plans and eventually managed to charm the Slavophiles – a movement supporting the unification of Slavic peoples – into lending him money. Yet surprisingly, Ashinov thought better of the idea that he could just run away with the funds.

Ashinov went to Poltava (a town in modern-day Ukraine) to recruit the poorest among the peasants. Promising them mounds of gold, he persuaded roughly a hundred families to relocate.

While the peasants were packing up, Ashinov made a pact with the authorities of Sukhum – a city on the eastern coast of the Black Sea. Local authorities decided that new settlers (even if they didn’t come from Kurdistan) would amount to more taxes and positive reports to officials. As a result, Ashinov was given some land and starter money. He ‘modestly’ decided to name the new village after himself – Nikolaevskaya.

Many peasants grew disappointed once they arrived – the land plots were a far cry from the “ataman’s” descriptions and the starter money wasn’t significant. Moreover, instead of using the allocated funds to buy and distribute cattle to the peasants, the scammer bought the cattle and resold it to the peasants at exorbitant prices. When district authorities became aware of this, they sent a group of auditors to Nikolaevskaya, but before they arrived, Ashinov fled to Moscow.

Once there, he met the poet Ivan Aksakov and the public figure Mikhail Katkov, whom he convinced that the Nikolaevskaya scandal was caused by stagnant Caucasus administration, which was unable to see the major national benefits behind his ideas. In order to restore his reputation and not sit idly, he developed a new, even more brilliant story. This time he expanded the limits of his “Cossack empire” to a shocking scale.

Preparations for the next venture

According to Ashinov’s story, the free Cossacks planned to grow tea in the mountains and had already sent emissaries to China. In the meantime, they were engaged in trade in Asia and East Africa. As for Russia, it needed to populate the Horn of Africa, which already had a Cossack town named New Moscow. The Abyssinian tsar of the time had promised the Cossacks land and all they had to do was come and take it! Moreover, Ashinov claimed he had been personally received by the Emperor of Ethiopia. Unsurprisingly, the article recounting this amazing story was written by none other than Ashinov himself.

Ashinov really did travel to Ethiopia but got no farther than the residence of a provincial governor. The fable was able to spark unprecedented excitement in the newspapers – journalists who had never been to Africa described crowds of Cossacks secretly living in Sudan and in the wilds of the upper Nile. The “ataman” took active part in social events where he behaved audaciously and told stories worthy of an Indiana Jones movie.

Ashinov turned out to be an apt psychologist and found a personalized approach to people. Journalists were easy prey since they were always looking for a sensation, but Ashinov went further. He enticed priests with unprecedented prospects for the development of Orthodox Christianity in Africa; tempted military commanders with images of future harbors for the navy; and even charmed the governor of Nizhny Novgorod with the prospect of becoming the ruler of an overseas colony.

Some of Ashinov’s patrons saw through the charade. For example, the chief prosecutor of the Synod, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, was far from an enthusiastic youth – a shrewd intellectual, he had no illusions concerning the man. However, he felt that if Ashinov were to succeed, he could be useful for the government and if not, the authorities could disown him at any time. Emperor Alexander III called Ashinov “that scoundrel” and decided that if the self-appointed ataman of the African Cossacks wanted to build some kind of colony, he could have fun at his own expense – the treasury would not provide a ruble.

Ashinov did not object. In the spring of 1888, he indeed sailed to Africa, searched for a suitable place for a colony, got to know the locals, and returned to Russia. In December of the same year, he sailed from Odessa to Africa on a steamer packed with “free Cossacks.”

Russian Africa

There were only two real Cossacks aboard the steamer. Most of the colonists were school dropouts, expelled officers, crooks, drunkards, and reckless adventurers. On the way, they robbed a gambling house in Port Said, got drunk, made mischief, and took prostitutes along for the journey. The voyage was quite jolly, and only blind optimists would have bet on the success of the enterprise.

In January 1889, the whole company disembarked in the Gulf of Tadjoura in what is now Djibouti. Locals from the Danakil tribe stared at the exotic newcomers. The favor of the local “sultan” (whose palace was a hut made of twigs) was ensured when the settlers gifted him pants.

To gain a foothold on the coast and create a kind of outpost for moving inland, Ashinov needed to find lodgings. The abandoned Egyptian fort of Sagallo proved just right. He proclaimed the fortress Russian, dubbed it New Moscow, or Moscowskaya village, and proclaimed that "fifty versts [old Russian measure of length, equal to 0.66 mile] along the coast and a hundred versts inland is Russian land.” On January 28, the Russian flag was raised over Sagallo.

The “Cossacks” cultivated the land and hunted. The land was fertile, and the surroundings teemed with wildlife and fish. Many of the former hooligans actually began to start a new life. Ashinov even managed to hold a prayer service on the occasion of the new lands joining Russia.

Unfortunately, the adventurer made a fatal mistake when choosing the location for the new colony.

Paris strikes back

The Russian government initially stipulated that the “Cossacks” could fool around as much as they wanted to, as long as they did not cross the territory of other states. However, the surroundings of Sagallo belonged to the French Colonial Empire. Since there was not a single Frenchman visible around for miles, Ashinov either did not understand that he had chosen territory that was already claimed, or just brushed it off as irrelevant.

When word reached Paris regarding events near Sagallo, the French were shocked and requested an official explanation from St. Petersburg. Emperor Alexander III, who barely tolerated Ashinov, became enraged and declared that he was a charlatan who had nothing to do with the government of the Russian Empire. A Russian warship was sent to Sagallo to retrieve the Cossacks.

But the French arrived first.

A few weeks after the colony was founded, four French ships approached Sagallo and demanded the “Cossacks” leave. Ashinov did not understand the seriousness of the situation and chose to ignore the warning. Then the French opened fire.

The first shell struck a family of colonists and killed five people, all of them women and children. The ships fired for another quarter of an hour, killing one other person and injuring 22 people. Finally, Ashinov put out a white flag.

The colonists were arrested, but after a short while they were taken back to Russia and Sagallo was destroyed. Incidentally, Emperor Alexander blamed Ashinov for everything that happened, but the French public sympathized with the “Cossacks” – after all, they did not do anything to justify being fired on by the ships.

Alexander III was extremely angered by the incident and initially wanted to exile Ashinov to the harsh Siberian environment of Yakutsk. Fortunately, the Emperor eventually cooled down and allowed the “ataman” to relocate near Chernigov, where he finally settled down and applied his energy to more useful things. The former con artist laid out a large garden, set up an apiary, and found a legitimate source of excitement by establishing and leading a volunteer fire brigade. Oddly, there was one object in his house that was a poignant reminder of his adventuring days – a gold-trimmed saber bearing the Greek inscription “To Justinian the Great,” the origin of which remained a mystery. The master illusionist remained true to himself until the end.