Decolonization of a name: What does ‘Bharat’ mean and will ‘India’ disappear from the world’s maps?

“Mera Bharat Mahan [my great India],” shared legendary matinee idol Amitabh Bachchan on X. “Team India nahi, Team Bharat [not Team India, it’s Team Bharat],” posted former cricketer Virendra Sehwag, who proclaims himself a “Proud Bharatiya.” These were among the few subdued remarks made after government communiqués sparked rumours on Tuesday that India may be renamed Bharat, leading to fiery debates for and against such a rechristening.

It started with an invitation to a G20 dinner with a letterhead reading “President of Bharat” (the G20 group’s summit opens in Delhi in a few days). Another referred to Prime Minister Narendra Modi as the “Prime Minister of Bharat.” In the ensuing uproar, experts were quick to highlight Article 1 of the Constitution of India, which reads, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.” This, they argue, does away with the need for any name change.

However, social media is abuzz with how “India” is the result of a colonial hangover (Pakistan founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah is also believed to have objected to it, preferring the name “Hindustan” instead), and how the “Hindu” nation deserves an identity closer to its roots. So RT is unearthing the true origins of “India” and its etymological and linguistic history.

India and Bharat

An online search for the “names of India” turns up, among many things, articles titled “The 5 names of India,” “The 9 names of India” and one that even says “The 15 names of India.” While “India” hasn’t faced any real challenge besides public-interest litigation here and a party manifesto there, the debate dates back to September 1949, at the Constituent Assembly drawing up the Constitution. When Article 1 was read out as “India, that is Bharat…” various other suggestions were made, including the use of “Bharatvarsha,” “Bharat or, in the English language, India” and “Bharat, known as India also in foreign countries (sic).”

“The reason we have so many of these different names is because they were given by different cultures,” says assistant professor Kanad Sinha of Kolkata Sanskrit College and University. “Also, the landmass we now know as India was a creation of 1947. There was a perception of a common larger territory before then.”

When Indian nationalism was on the rise, political organisations adopted the name “India,” like the Indian National Congress, established in 1885. Even Queen Victoria took up the title of the “Empress of India.” But similarly, “Bharat” was also familiar to the people. The Bharat Sabha, for example, was the precursor to the Congress, implying that both terms were in simultaneous use.

India’s various monikers have referred to no particular politically unified territory but to simply a geographical area bounded by the Himalayas in the north, the ocean in the south, and fluid eastern and western boundaries. The supposed colonial nature of “India” begs the question: what did the inhabitants of this region call it themselves?

Our very many names

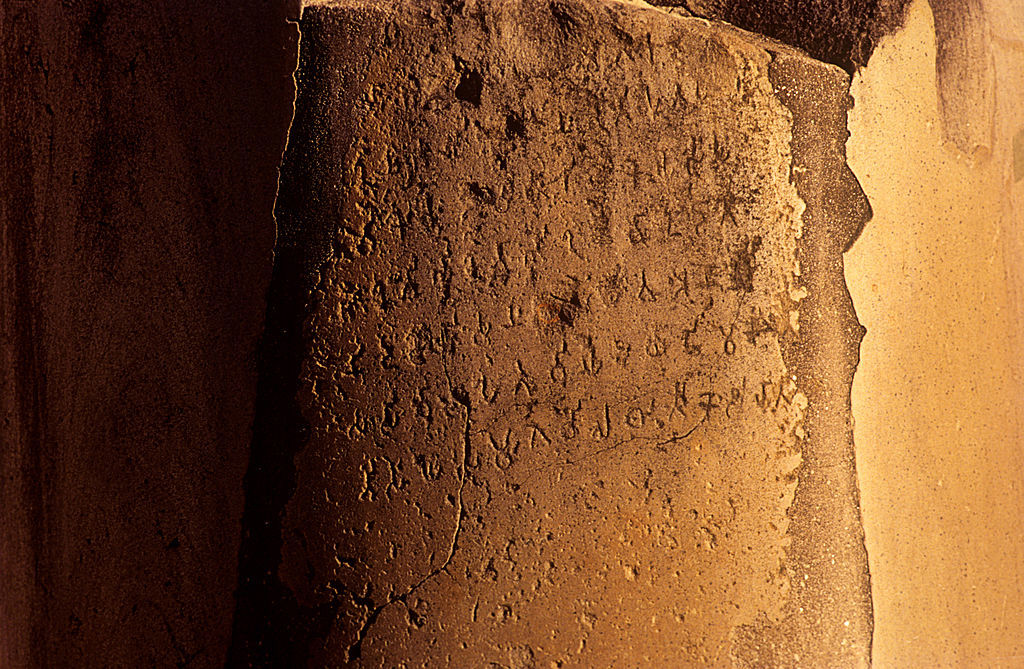

Meluha is believed to be one of the oldest names, coined around the time of the Harappan Civilisation. Mesopotamian records, however, show that Meluha is what others dubbed it, not the Harappans themselves, because their script has not been deciphered.

Jambudvipa or Jambudweep was used in Ashokan inscriptions as well as early Buddhist texts and Puranic texts later. “Ashoka probably knew the entire subcontinent as Jambudweep—his own political territory and also the southern regions beyond that were under dynasties of the Cholas, the Pandas, the Satyaputras and the Keralaputras,” says Sinha.

The ancient Chinese, Koreans and Japanese called the subcontinent Tianzhu, Cheonchuk and Tenjiku, respectively (the words loosely translate to heaven). Ancient texts also refer to India as Nabhivarsha because Nabhi was believed to be the son of the man who once ruled the planet. Another inference is that in Sanskrit, “nabhi” is the navel, and India appears to be the centre of the Earth on a map.

Aryavarta and Dravida were the names of the regions divided by the River Narmada. The former northern and southern halves, respectively, find mention in the ancient texts ‘Manu Smirti’ and the ‘Hindu Puranas.’

Ajnabhavarsh has its roots in the Vedic story of creation. Bharatkhand is mentioned in several ancient Indian texts. Himvarsh refers to the Himalayan region.

The ‘Puranas’ (circa mid-first millennium CE) perceived the world as seven continents (not the seven geographical territories we know today) spread out as concentric circles. Jambudvipa was the central continent (larger than modern India) divided into seven ‘varshas,’ of which one was ‘Bharatvarsha.’ The Puranic concept of Bharatvarsha is similar to today’s territory, as described in the Vishnu Purana (circa 4th century CE).

The Sindhu River: The root of Hindu and India

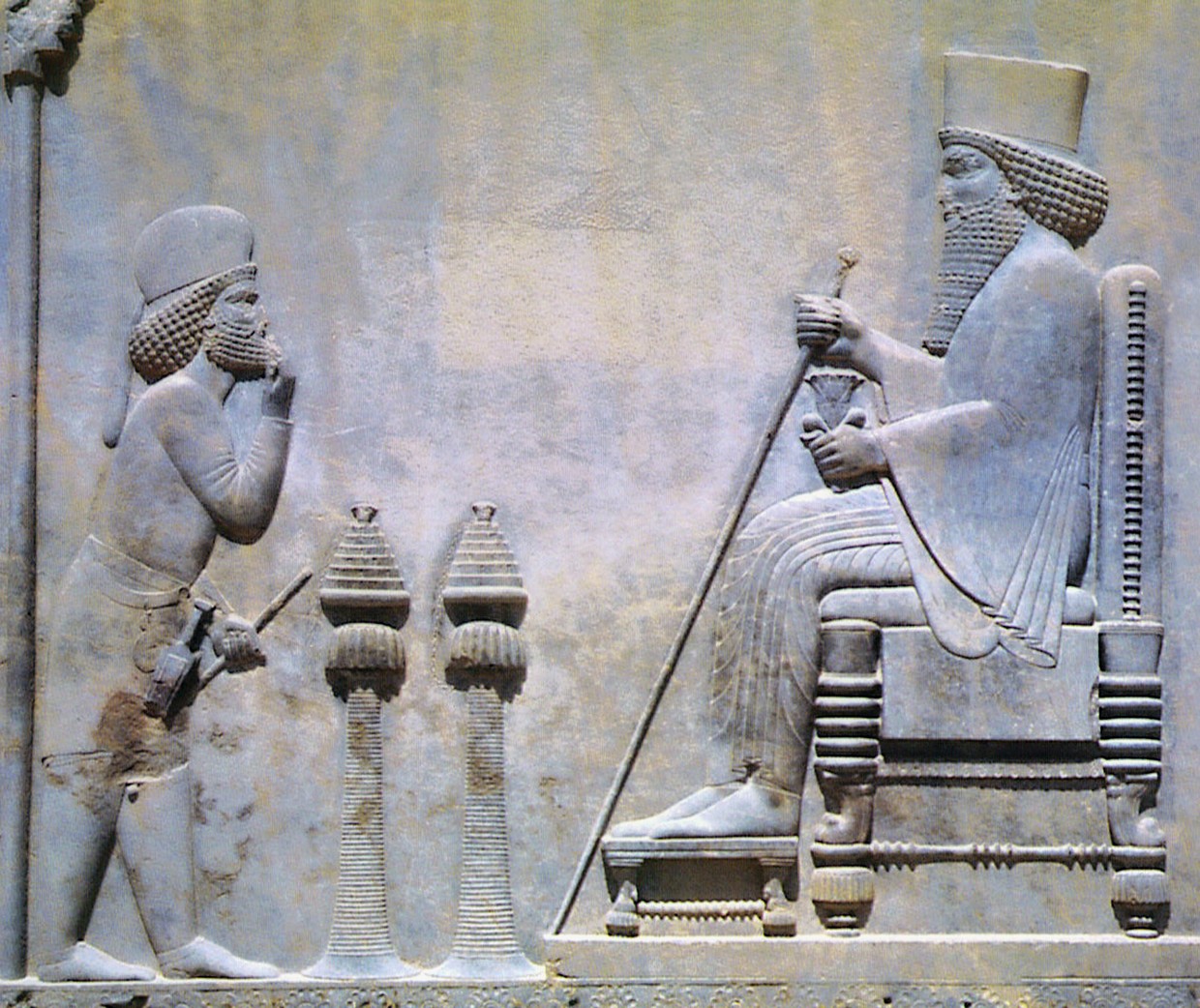

The words Hind, Hindu and India are geographical in nature, originating in the River Sindhu, or Indus, a landmark that invading armies first encountered. One of the earliest references, says Sinha, is by Persian emperor Darius, who conquered parts of the subcontinent’s northwest in 518 BC. From the sculptures of his soldiers, we get the term “Hidus” and “Hindus,” which were derived from the Sanskrit Sindhu. This, in Persian, becomes “Hindu,” and “Indus” in Greek.

The Greeks only knew of the subcontinent from the Persians and had not directly encountered it. Greek historian Herodotus adopted the Persianised “Hinduka” in his literature. It was in 326 BC that the Greeks came into direct contact when Alexander invaded the Persian Empire and moved east. The region was hellenised as “Indos,” “Indoy” or “India” from the Persian “Hindus,” referring to territories beyond the Indus Valley.

The suffix “ya” was added to territories’ names; so, like Russia and Serbia, India came about. Persians preferred “-stan,” like Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. “Hindustan” and “India” are thus “more or less the same words,” Sinha adds.

The Persian “Hindu” was rendered further into vernacular use following the Mughal invasion of India in 1526 (emperor Babur called the forces of Ibrahim Lodhi “Hindustanis” in Babarnama). “Hind” and “Hindu” travelled to Greece and became “Indus,” “Inde” and, finally, “India.” These gradually made their way to Latin and other European languages, including English. Arabic and related languages such as Urdu, however, retained the “H,” due to which the Turks and Mughals continued to know “India” as “Hindustan.”

Originally, the word “Hindu” had no religious link. It was only later assumed by Europeans, who began to refer to the country’s indigenous as “Hindu.”

The complicated history of Bharat

“Bharat” has a much older origin in the Rigveda, India’s oldest known text that is said to have been composed around 1420 BC, when nomadic tribes migrated to the region. The Bharats were the most prominent among these tribes. “Bharata” was thus used in reference to the dominion of the descendants of Bhārata, believed to be the first universal ruler and the most distinguished of the early Vedic clans.

“These tribes, or janas, had no settlements initially but in the later Vedic period between 1000 to 600 BC, they moved eastward, adopted agriculture as their profession and began to settle down in areas that became known as janapadas,” says Sinha. “The Bharatas also fused with the Puru tribe to become the Kurus; their janapada was named Kurukshetra.”

These clans became royal dynasties and their names turned into names of kings. “Thus were born the mythical kings, Bharata, Kuru and Puru... And this is why the epic that describes the events of the Kuru-Panchala kingdoms is known as the Mahabharata,” adds Sinha, whose ‘From Dasarajna to Kurukshetra’ is a scholarly exposition on the making of an ancient Indian historical tradition.

As the Puranic genealogies expanded, it was eventually argued that all the kings of India were related to this mythical king, Bharata. And thus was established the idea of Bharatavarsha.

The India and Bharat dualism

In the India versus Bharat debate, conservatives believe the latter proudly connects to our indigenous ancestry, which the former avoids. Also, its popularity was secured further during the freedom struggle in slogans such as “Bharat Mata ki Jai” (“Victory for Mother India”). India, on the other hand, is perceived as a term of foreign origin.

Not unlike how city-dwellers feel that “Mumbai is a city, Bombay is a sentiment” a similar such differentiation exists between India and Bharat. The “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav” held in Delhi in December 2022, for instance, had as its theme “Where Bharat Meets India,” underlining that the two are perceived as separate entities.

“The Constitution adopted ‘India, that is Bharat…’ because it was committed to this pluralistic idea of India, that this is a country of multiple cultures, languages and histories,” says Sinha. “These various names carry the weight of the multicultural history of the Indian subcontinent.”

He further elaborates: “When we try to affix only one name, one that sounds similar to its reference in only a few native languages, it brings with it the imposition of one cultural identity, eradicating all others. Calls for a change of name arise every now and then because there’s a clash between these two ideas—whether we continue our multicultural, pluralistic identity, or whether we want to make it only a monocultural, monolithic community.”