Trams rights: Citizens of this former colonial capital are rising up to protect Asia’s oldest electric transport system

On October 5, a protest rally blocked College Street in the heart of Kolkata, in the eastern India state of West Bengal. It was a motley group: Students, people from different professions, and senior citizens, out to save a part of the city’s identity – Asia’s oldest tram service, running for over 152 years.

The group was small considering the city’s political culture but the social media outcry was much bigger. The city’s trams may have become a marginal option for commuting, with a steady decline in the last few decades, but they are strongly associated with the city’s heritage and are part of its cultural pride.

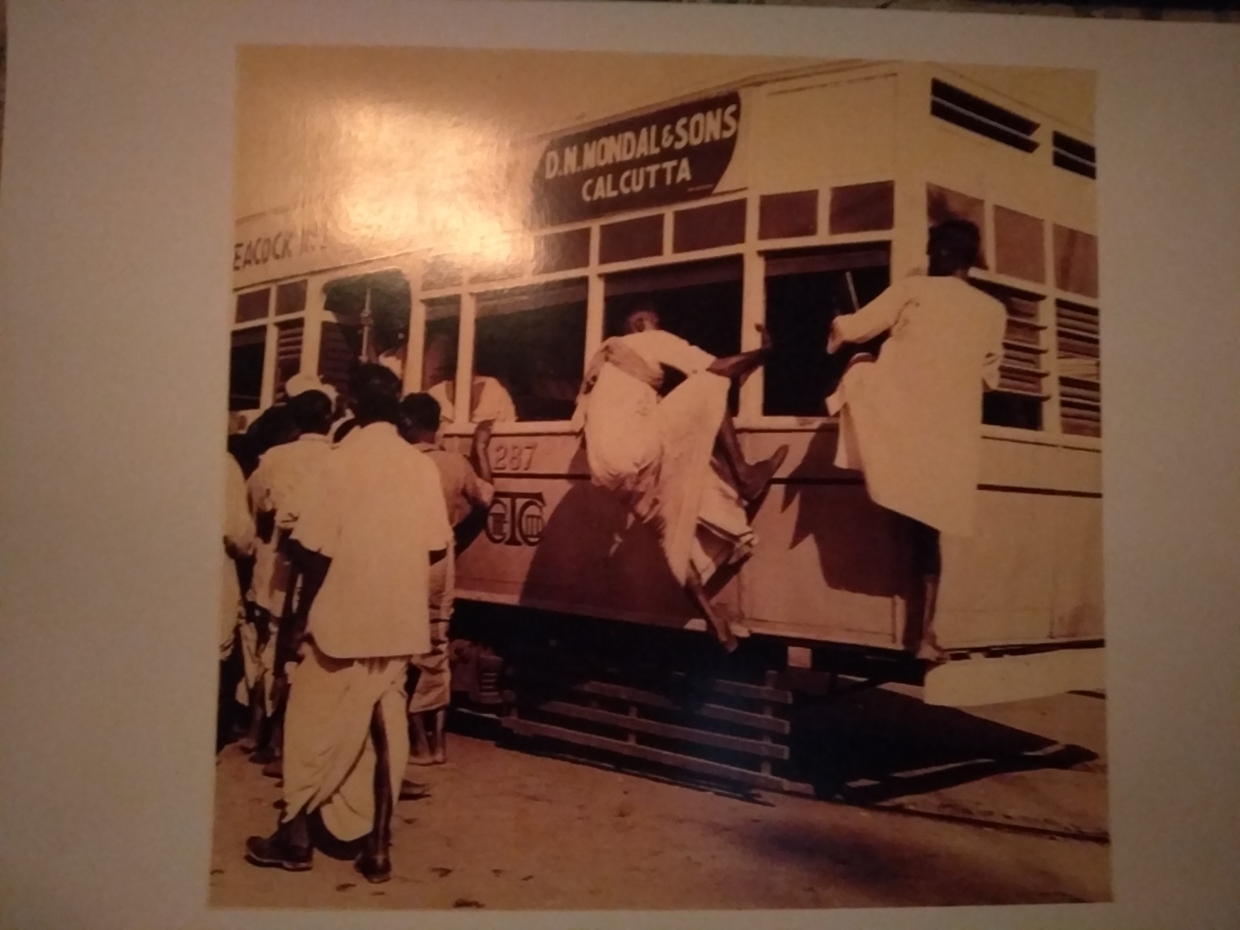

The first horse-drawn trams in Kolkata began service in February 1873, covering a 3.9km route from Sealdah to Armenian Ghat Street near the Hooghly River. In 1882, steam locomotives were introduced to pull tram cars through the city streets, aiming to replace the horse-drawn system. In 1902, Kolkata became the first Asian city to have an electrified tramway. Today, this is the only operational tram system in India.

West Bengal’s transport minister, Snehashish Chakraborty, stirred the hornet’s nest last month, announcing that the government plans to do away with trams. After a series of protests, the minister has now said that it will not happen immediately. The respite for citizens is that the issue of phasing out trams is still pending at the Calcutta High Court; a judgment in June last year was for restoring and maintaining trams.

This was not the first time that the state government made such an announcement. The administration has had a strained relationship with trams right from the late 1980s when they were declared unprofitable and cumbersome to run.

The outcome of this was that by 1992, the number of trams and their frequency went down sharply, and the Calcutta Tramways Company also started operating buses. Currently, trams operate on only three routes in the city.

Ironically, the period of decline of trams in Kolkata was also the period when cities in Europe and elsewhere were actually rejecting the idea of phasing out trams. They were reviving their tram services as a cleaner mode of transport, evolving from a phase from the 1940s to the 1970s when many countries had phased out their trams.

In the UK, which had scrapped half of its trams by 1940, cities like Manchester, Sheffield, and Birmingham reintroduced light rail in the 1990s. Other countries such as France, Russia, Portugal, and China have now introduced or revived tram networks.

France, which had reduced its tram operations to just three in 1966, now runs 28 tram systems. China has introduced tram systems in different cities such as Qingdao, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Wuhan, and Beijing. In recent years, Russia has seen a tram boom with the introduction of new models and experiments with self-driving trams after it shut down some of its services in the 1990s. Moscow has 38 tram routes.

The government mostly remained aloof to global developments and debates but it did influence some people in Kolkata. One of them was retired scientist Debashish Bhattacharya, the founding president of Calcutta Tram Users Association (CTUA). For the last three decades, he has conducted many awareness campaigns and even took the government to court to reopen tram routes.

Apart from supporters in the city, he also found important support from other parts of the world. Among them, Roberto D’Andrea, a tram worker from Melbourne, is now a part of the city’s culture. He first visited Kolkata in 1994 and found the tram service in shambles.

Together with tram workers and activists in the city, he designed ‘tramjatra’ (‘jatra’ is an open-air performance), a moving carnival where the trams were painted and decorated and the conductors put on cultural performances with dance, drama and poetry during the tram ride.

As a part of this carnival, they also ensured technical exchanges which led to some tramway revival from the early 2000s. The state government too pushed funds to the Calcutta Tramways Company to build new trams, and repair and upgrade the overhead electrical systems.

“With all this in place already, Kolkata’s tramways could be rebooted without much expense. Tram tracks are in good condition and there are many operational trams stored in depots. It would be tragic if the system was closed,” D’Andrea says.

But after that initial push in 2000, the government has not been active in reviving trams and the decline continued. The number of operating trams has come down from about 180 in 2011 to about 37 in 2018 and less than 20 now, according to data collected by CTUA. Many of these trams now are kept unused in depots.

This may come as a surprise to some, given the state government’s celebration of the tram as a cultural icon in the last few years. There have been multiple government initiatives with trams – a tram with a library, air-conditioned trams, trams with WiFi, a tram designed as a tribute to the jute industry and a depot turned into a tourist spot to see old trams.

Bhattacharya feels that this does not address the real issue. “Trams are being reduced to just a heritage to be maintained in some corner. While it is important to celebrate history, we are missing the point that trams are a convenient, profitable and most importantly cleaner mode of transport,” he says.

While there is no doubt that the number of people using trams is very low in Kolkata now, the reason for that is not that trams are not effective, says Bhargab Maitra, an urban planner and professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur.

“The modern AC buses introduced in the last two decades have worked well in Kolkata but what if their frequency is reduced. Will they work? That is exactly what is happening with trams. Trams have been reduced to such an extent that they have become ineffective. There is no reason why people will not use a safe, effective public transport mode if it works,” he says.

Maitra points out that unlike in Europe or China, where there has been ample modernization of trams, whether it is faster moving streetcars or more comfortable, air-conditioned ones, there has hardly been any modernization here. Instead, the neglect has led to other problems. Like only a few tram stops allow people to alight near the pavement or in a gap safely and avoid oncoming vehicles.

“Somehow the popular perception of debate is that it is between nostalgia mongers on the one side and those looking for a practical way to run budgets. But that is not the case at all. Cities across the world are not running trams to cater to nostalgia,” he says.

There are more complaints against trams from the city administration. Transport Minister Chakraborty echoed that when he again said that trams are slow and contribute to traffic jams, and that the city’s roads are too narrow to accommodate both trams and other vehicles.

But urban planners differ. In fact, in many cases trams have reduced traffic congestion, points out Shreya Gadepalli, South Asia Director at the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy.

“A tram can carry two hundred people but with a footprint of just five cars. What we urgently need is modernization of trams so that those travelling in cars will also opt to travel by trams,” she says.

Maitra adds that there have been similar car centric approaches to decongest roads which have not worked in the long run. Like reducing pavement space to widen roads. “But when we study these roads in the long run, there is no major difference,” he says.

Multiple cities such as Prague, Budapest, and Lisbon have exclusive right of way for trams, which make it safer and more convenient, Gadepalli says.

But they all agree that the tram system that the city needs cannot be the way it is now. For a city like Kolkata with a population of over 4.5 million people, its trams need to run faster and be more convenient to use.