Gates Foundation focuses $3bn agro-fund on rich countries, ‘pushes GMO agenda in Africa’

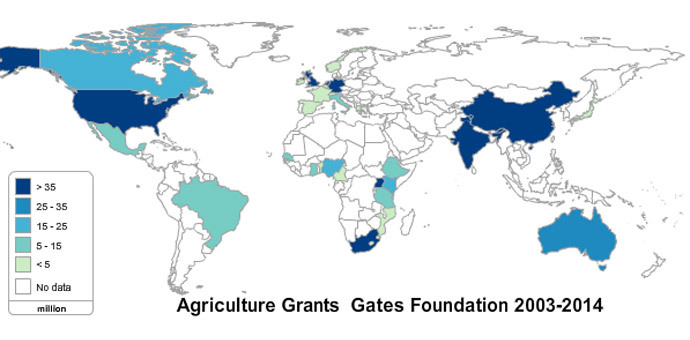

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation gives the majority of its $3 billion in food and agricultural grants to rich Western countries, with critics accusing it of using its money to force a pro-GMO agenda on Africa, a recent report suggests.

GRAIN, a small international non-profit, made its accusation after breaking down the foundation’s distribution of grants handed out between 2013 and 2014.

Roughly $1.5 billion ends up in the hands of hundreds of different research, development and policy organizations, 80 percent of which are based in the US and Europe. Only 10 percent of those groups, meanwhile, are in Africa.

READ MORE: Ebola epidemic might trigger major food crisis - UN

The charity further notes a deepening of the so-called North-South divide via the allotment of money to non-governmental organizations. Of the $669 million the foundation earmarks to NGOs for agricultural work, GRAIN says over three-quarters has gone to US-based organizations. Africa-based NGOs, by contrast, only receive 4 percent.

GMOs and tech

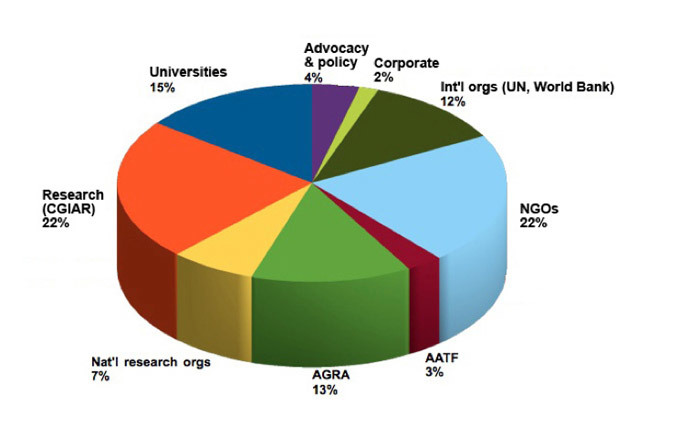

The other half of the $3 billion fund is allocated to 4 distinct groupings.

The first, CGIAR, a consortium of 15 international research centers set up to promote the Green Revolution across the world, has received $720 million from the foundation. According to GRAIN, most of the CGIAR centers dedicate their money to developing new crop varieties.

READ MORE: Monsanto's ‘healthier environment’ ads banned in South Africa

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), which was set up by the Gates Foundation, receives $414 million. International organizations, including the World Bank and World Food Program, take in $362 million, while the Nairobi-based African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) has received $95 million since 2008.

AATF, which GRAIN characterizes as “a blatantly pro-GMO pro-corporate research outfit,” reportedly uses its funding to support the development and distribution of hybrid maize and rice varieties. GRAIN further says AATF uses money received by the Gates Foundation to “’positively change public perceptions’ about GMOs and to lobby for regulatory changes that will increase the adoption of GM products in Africa.”

Meanwhile, the massive chunk of money going to CGIAR fuels criticism that the foundation is giving its money to scientists rather than farmers.

In the same time period that CGIAR received $720 million, the Gates foundation gave $678 million to predominately western universities and national research centers. It further claimed the Gates Foundation’s support for AGRA and AATF closely mirrored this research agenda.

Programs for research or technology development carried out by farmers themselves or based on farmers' knowledge, meanwhile, were all but ignored, the NGO claimed.

“The foundation has consistently chosen to put its money into top-down structures of knowledge generation and flow, where farmers' are mere recipients of the technologies developed in labs and sold to them by companies,” GRAIN wrote.

Richard Wolff, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, told RT that the “absurd way” the Gates Foundation allocates funds is a reflection of how the charity is set up.

“The final decision of who gets the money is in the hands of Bill and Melinda Gates. They are not farmers. They are not people who know much about agriculture. So whatever decisions they made, they got more or less information from more or less qualified advisors who they also chose,” Wolff said.

Political meddling?

While the NGO says the Gates Foundation does not directly intervene in the affairs of African states, AGRA, which has received $414 million since its establishment in 2006, is said to focus at least some of its work on “shaping policy.”

“AGRA intervenes directly in the formulation and revision of

agricultural policies and regulations in Africa on such issues as

land and seeds. It does so through national ‘policy action nodes’

of experts, selected by AGRA, that work to advance particular

policy changes,” GRAIN writes.

The organization cites strenuous efforts by The Ghana Food

Sovereignty Network to block policy revisions to the country’s

national seed policy drafted by AGRA as one example of policy

interference carried out by the foundation. Mozambique and

Tanzania have also seen AGRA-directed meddling in the country’s

seed policy.

The study further notes that one AGRA action plan for Tanzania

called on a review of “laws governing land titling at the

district level” and a need to work close with district officials

“to develop guidelines for formulation of by-laws.”

Grain says The Gates Foundation, which states “listening to

farmers and addressing their specific needs” as a guiding

principle of its agricultural work, has turned a deaf ear to

Africa’s small-scale agricultural workers.

“In practice, the foundation's first guiding principle

appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to

farmers,” GRAIN writes. “In that, it looks, not

surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft.”

While the NGO says the Gates Foundation does not directly intervene in the affairs of African states, AGRA, which has received $414 million since its establishment in 2006, is said to focus at least some of its work on “shaping policy.”

“AGRA intervenes directly in the formulation and revision of agricultural policies and regulations in Africa on such issues as land and seeds. It does so through national ‘policy action nodes’ of experts, selected by AGRA, that work to advance particular policy changes,” GRAIN writes.

The organization cites strenuous efforts by The Ghana Food Sovereignty Network to block policy revisions to the country’s national seed policy drafted by AGRA as one example of policy interference carried out by the foundation. Mozambique and Tanzania have also seen AGRA-directed meddling in the country’s seed policy.

The study further notes that one AGRA action plan for Tanzania called on a review of “laws governing land titling at the district level” and a need to work close with district officials “to develop guidelines for formulation of by-laws.”

Grain says The Gates Foundation, which states “listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs” as a guiding principle of its agricultural work, has turned a deaf ear to Africa’s small-scale agricultural workers.

“In practice, the foundation's first guiding principle appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to farmers,” GRAIN writes. “In that, it looks, not surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft.”