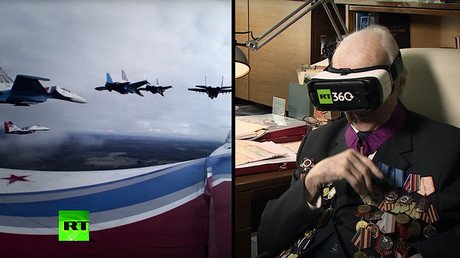

‘We were schoolchildren thrown into war’: WWII hero recalls bravery & horror on Eastern Front

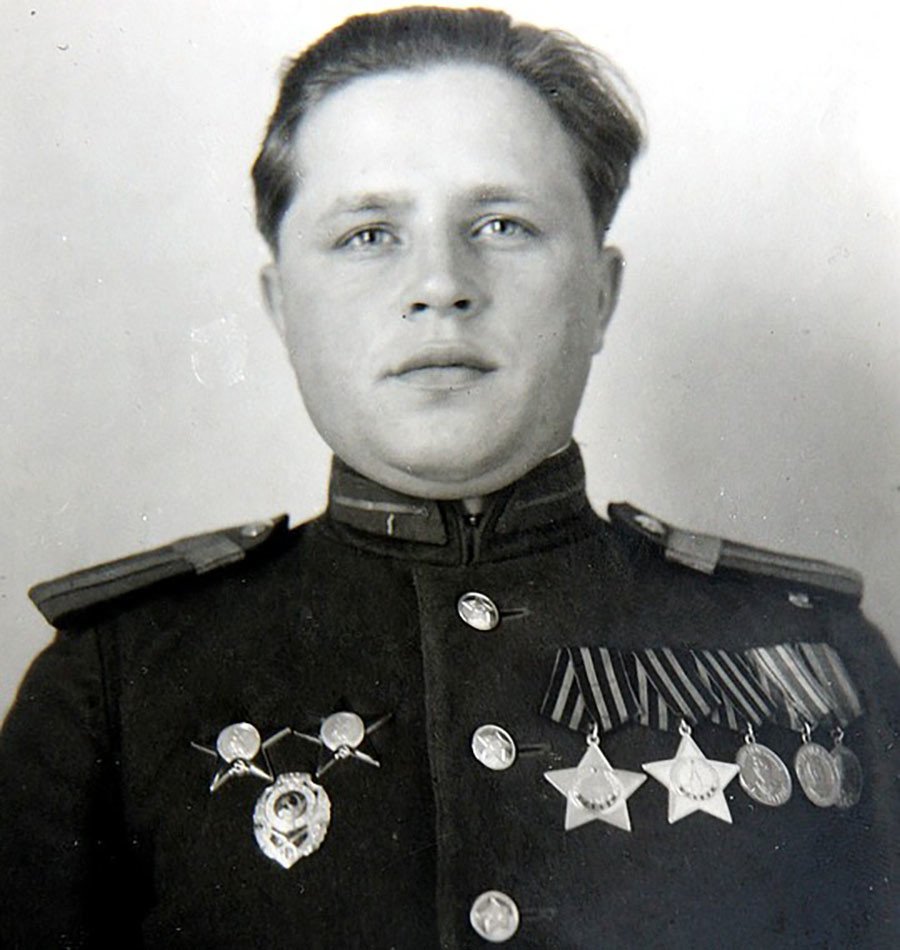

One of the most decorated World War II veterans still alive, 91-year-old Konstantin Fedotov, talks about being drafted as a teenager, what makes a good infantry scout, and the images still seared into his mind more than 70 years after the conflict ended.

Konstantin was a 15-year-old schoolboy when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, and he still vividly remembers the “pervasive unease” he and his classmates felt, anxious for snippets of news on radio, realizing their lives had irrevocably changed.

Within weeks, entire columns of young men were marching west from his village outside Gorky, now known as Nizhny Novgorod.

“We all had tears in our eyes, but convinced ourselves we’d see them again,” he told RT on the eve of the Victory Day celebrations. “Some came back within months, crippled and unable to return to the frontlines. Others fought the length of the war. Many never returned at all.”

In a single year, his older brother, and three of his father’s siblings were killed, their remains buried across the Eastern Front.

With almost every working-age man gone or incapacitated, Konstantin spent the first two years helping out on the collective farm.

But in November 1943 he received his own draft notice. He became part of the last wave of men recruited en-masse into the Red Army, and is amongst the youngest survivors to have fought through a substantial part of the war.

It was after Stalingrad and Kursk. The conflict had been turning in Soviet Russia’s favor but the Red counteroffensive required a large recruitment of manpower.

“We were sent up to train, but we never did finish our training – we were just a group of teenage schoolchildren thrown into the war,” says Fedotov.

He was assigned to the Belarussian front, just as the Red Army was about to execute its most outstanding World War II offensive, Operation Bagration.

Although sent up as an infantryman, once posted, the recruits had a chance to volunteer for various units.

“I begged to be a scout. To be one, they said that you had to physically developed, resourceful and psychologically stable – and I must have had some of those qualities they were looking for.”

Having to spend consecutive days in small groups, and always in at least a degree of danger, the scouts developed tight bonds and absolute loyalty to each other.

Fedotov’s unit specialized in raiding advanced enemy outposts to capture enemies, who would then be interrogated until they revealed positions and battle plans. Often, these would be night operations, “during which a minute always seemed like a day.”

Scouts were also the first to see the raw impact of the German occupation, and the destruction left behind by the retreating Nazis. There were burned villages, charred corpses of civilian – mostly women and children.

“The atrocities were blood-curdling. But because we were advance teams, we couldn’t do anything but keep our emotions in check.”

There were also interludes of more conventional gun battles, such as the recapture of Mogilev, where the Soviets had to advance street-by-street through fortified German positions.

It is here that Fedotov was awarded the first of his two Orders of the Red Star for courage in battle – when he threw a grenade into a machine gun nest, then jumped through an open window and defeated several soldiers in hand-to-hand combat, before capturing their commander alive.

As his division crossed past the Soviet border, into Eastern Europe, “even a private could feel that the victory was coming.”

“The Germans must have understood this as well, but they kept fighting to the very last day, and they stayed loyal to their oath. They also realized that we knew of the brutalities they had inflicted upon our country,” explains Fedotov.

Stalin’s advance might have appeared unstoppable on maps, but as the Red army approached Berlin, the fighting grew more intense, and every death more tragic.

“After four years of war, we instinctively knew their every move, and they the same for us. The last battle was the hardest – the adage is true – by the end, even the children and the old men were fighting to the death.”

The war ended but Konstantin Fedotov never returned to civilian life. He graduated from a military academy, and joined the rocket forces, before retiring in 1995. He immediately became a member of a veterans committee and remains a touchstone figure for the dwindling number of heroes commemorating Russia’s most important victory.