‘My God, can this be happening?’ How the Romanovs faced their gruesome deaths

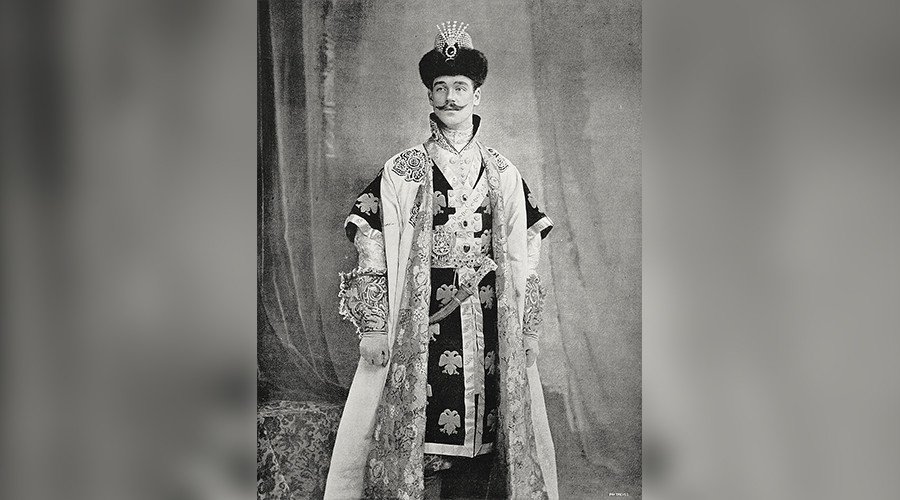

When they so casually surrendered their authority in March 1917, Nicholas II and the man he abdicated in favor of, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, could have barely imagined the mounting humiliations that would befall them in the coming months. And even in their hour of death they maintained the same demeanor of haughty dignity and otherworldly naiveté.

During his eight-day journey in a windowless freight train to his exile in the Urals in March 1918, Grand Duke Mikhail would have had plenty of time to ponder if he had done as much as he could to avoid this outcome. In and out of house arrest in the preceding months, Mikhail appealed to the British for asylum (rejected, just as was his brother’s application), packed his possessions for a journey to Finland (forbidden at the last minute), and wrote a letter to Vladimir Lenin, asking if he could change his name to Mikhail Brasov, after his estate (ignored). But he had made no concerted attempt to escape.

That is not to say that Mikhail Alexandrovich was reduced to anonymous penury upon his arrival in Perm, though perhaps it was his inability to blend in that sealed his fate.

Although initially placed in the prison hospital, the Grand Duke petitioned the Bolshevik leaders for better conditions and was soon installed at the Royal Rooms, the best hotel in the provincial town. With a pared-down entourage of just his valet, secretary and driver – the Rolls Royce was parked downstairs, but there were neither destinations to drive to, nor roads to drive on – Mikhail Alexandrovich had sufficient resources to maintain a caricature of his leisured lifestyle.

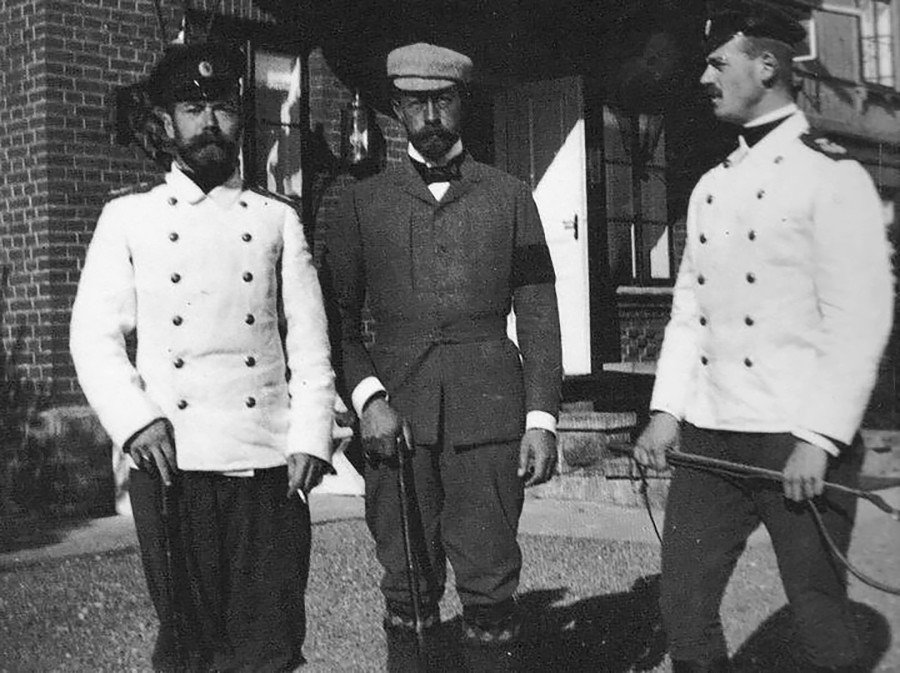

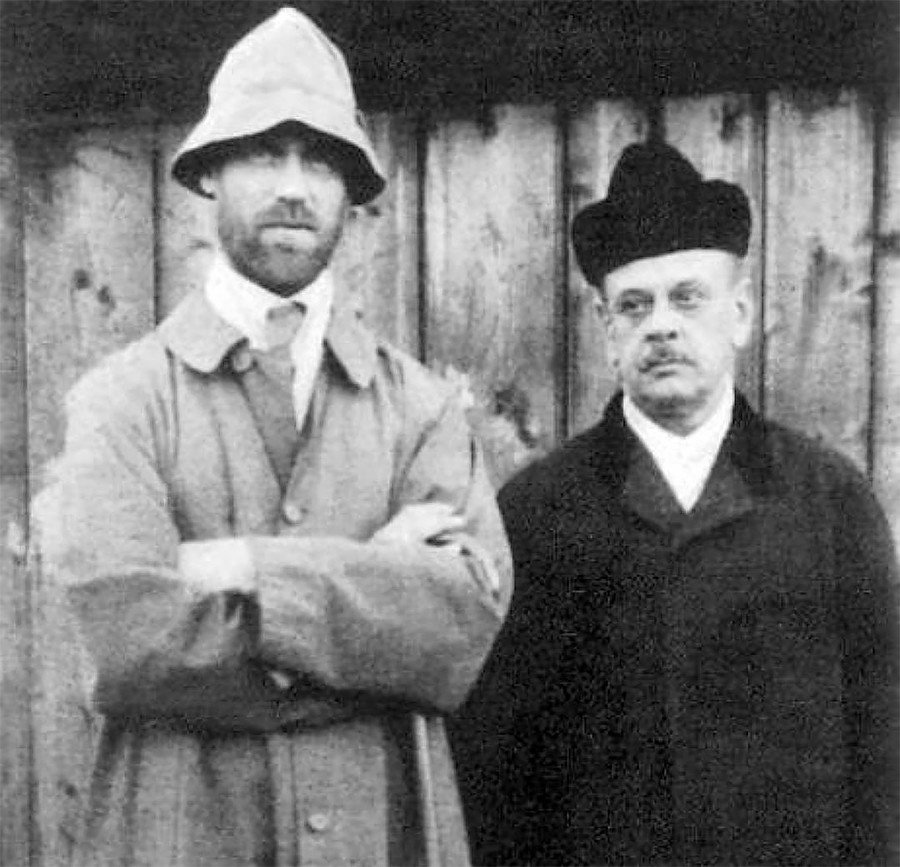

He took to strolling around the city center with his secretary Nicholas Johnson, before watching the opera from the balcony, always reserved. The tall, slender and genial royal, and his forlorn, stocky sidekick replicated the Little and Large dynamic that had amused the court for years. On the back of their last joint photo, Mikhail wrote that he “vowed not to shave his beard until his release.”

But Mikhail Alexandrovich was not the one setting terms. His local celebrity ballooned alarmingly. Destitute women would make pilgrimages to his daily route, a local cathedral made him and his visiting wife the guests of honor at an overflowing service, and a catch of fresh sturgeon from sympathizers was delivered to his room near-daily.

The noose tightened. Soon, to his incomprehension, he was to register daily with the local secret police that now observed his movements. His family seat in western Russia was nationalized, its treasures taken away by the coach-load.

The actual timing of the Grand Duke’s murder was precipitated by the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion, trapped in Russia and fighting their way out by taking a succession of cities on the Trans-Siberian Railway, while inside the industrial city, the Bolsheviks enjoyed a fragile support. Though he harbored no political ambitions and laughed off supporters’ suggestions that he should flee by saying his stature would make hiding difficult, local Communists feared the royal former war hero could become a figurehead for an uprising.

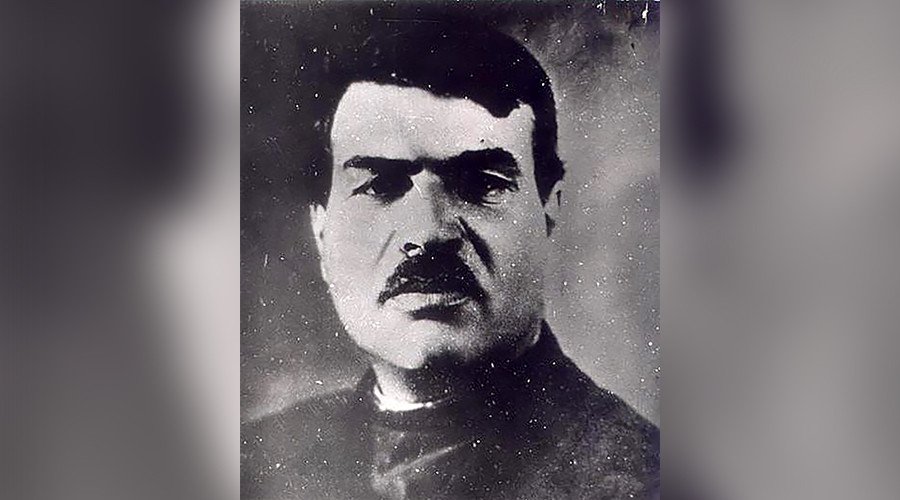

Still, while the responsibility for his death between Bolshevik leadership, the local Soviet, or a small group of professional revolutionaries has never been established with certainty, the Grand Duke’s murder was not prompted by any tangible threat, instead being a plot that veered between the cold-blooded and the amateurish.

In the late evening of June 12, 1918 a handful of conspirators arrived at Mikhail Alexandrovich’s hotel, where he was laid low with an ulcer, presented him with a fake evacuation order, which the royal refused to accept, demanding to speak to a senior official, and causing a commotion.

Still, Mikhail still had little inkling of what was about to happen, and asked Johnson to accompany him on the trip, which the conspirators allowed, and boarded the carriages outside.

The summary execution was crude. The phaetons carrying the two men went to the outskirts of the city, turned a hundred yards off the road near some woods, and stopped.

Ordered to get out, Johnson stepped out of the carriage and was immediately shot in the head. Next, the assassins aimed for Mikhail Alexandrovich. The first bullet grazed his shoulder, then one of the guns jammed. Now realizing that this was the end, the Grand Duke ran toward his secretary, begging to bid goodbye to him. As the killing threatened to turn into farce, the assassins finally plucked up their courage and unloaded one bullet after another into Mikhail Alexandrovich, who died next to Johnson.

The plotters then covered their bodies with branches, and returned the next day to loot and bury them.

The local Bolsheviks then published a fake story about the Grand Duke’s successful escape, and executed several dozen innocent local merchants for aiding it. The remains of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich and Nicholas Johnson have never been found.

‘We are readying ourselves for admission to the Kingdom of Heaven’

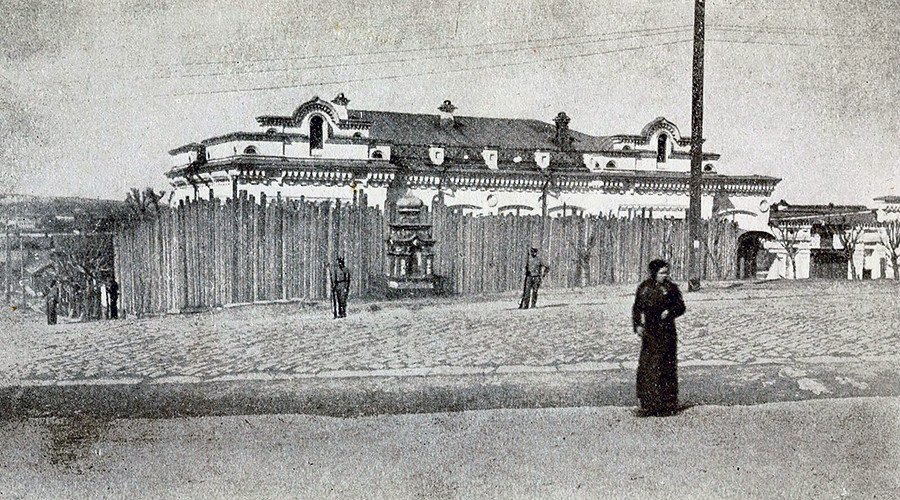

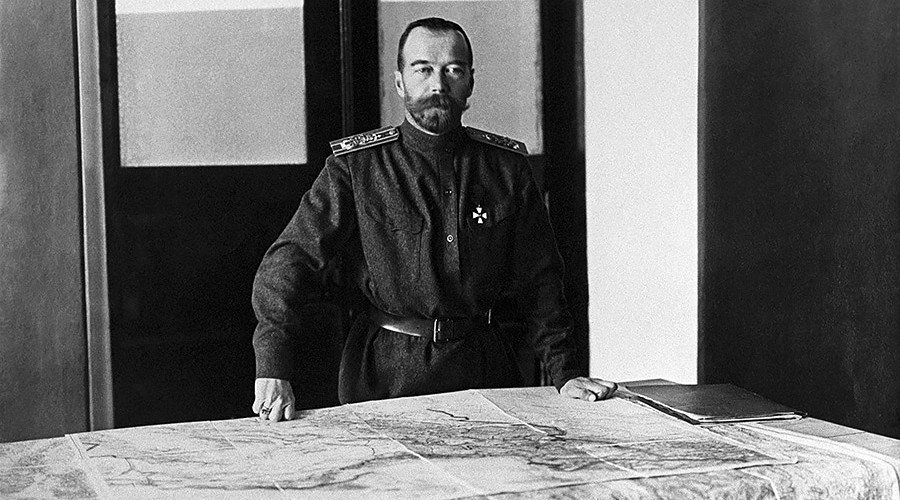

The double palisade around the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg, the 300 men guarding it, ever-stricter rations, curfews and rules – including having to ring a doorbell to go the lavatory – must have informed Nicholas II and his family of the downward trajectory of their destiny.

“We are readying ourselves for admission to the Kingdom of Heaven,” wrote the matriarch Alexandra Feodorovna of herself, her husband, their four daughters, and hemophiliac son Alexei, so crippled by knee trouble, he had to be carried.

Yet for all the fatalism, the family also retreated into oblivious delusion, occupying themselves with gardening and physical exercise, and when that was no longer allowed, card games and prayer, while secretly maintaining hope of being rescued.

Alexandra’s last diary entry on July 16, 1918 hints at no premonition of the horror of the coming night: “Gray morning, later lovely sunshine. Baby [Alexei] has a slight cold. All went out for 1/2-hour in the morning. Olga and I arrange our medicines. Tatiana read spiritual readings.”

Having retreated to bed at 10.30 pm after a game of bezique with his wife, the deposed Tsar Nicholas was awoken at midnight by a message from his executioner, Yakov Yurovsky, telling much the same lie as the one Mikhail questioned a month earlier – that they had to be evacuated.

Without resistance, the whole family dressed, the women putting on undergarments into which 10 kg of diamonds had been sewn, and proceeded down to the courtyard, and then a basement with no way out, before having to pose for their final photograph.

Finally, Yurovsky arrived and read out a one-sentence execution verdict to which an uncomprehending Nicholas answered "My God, can this be happening?" or, according to other accounts, simply “What? What?”

The women began to cross themselves, but before they completed the gesture, a bombardment of bullets pierced their bodies. The shooters were drunk, or scared themselves – firing through the doorway – and the precious stones both protected the condemned and prolonged their pain.

As smoke cleared in the room, the bullet-ridden royals still whimpered in pain, and Bolshevik soldiers began bayonetting their bodies, stabbing again and again. Even this was not enough to finish the job, and finally Yurovsky personally shot 13-year-old Alexei, propped up in a chair as he was too weak to stand, in the head twice.

From the first shot to the last death the execution took 20 minutes, leaving even several of the perpetrators queasy at the blood orgy.

The disposal of the bodies was yet grimmer: a baying mob of diggers pawing the bodies, tearing away their clothes as not just diamonds but pearls and gold spilled out; kerosene and 400 pounds of sulfuric acid to disfigure the skin; comical attempts to close a surprisingly shallow shaft by throwing down a grenade; two more attempts to rebury the bodies; more sulfuric acid; rifle butts to break down the skulls; concrete blocks to weigh the skeletons down. For all their ideological conviction, even the Soviets never publicly owned up to the events of this night, neither then, nor after all those involved were dead.

When the Czechoslovak Legion entered Ekaterinburg on July 25, 1918, it found no signs of the presence of Russia’s last royal family.