How Cassini's haunting Grand Finale unlocked Saturn’s secrets (VIDEOS)

On September 15, 2017 the NASA and ESA Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn ended when the probe was incinerated in the gas giant’s atmosphere. RT.com looks back at Cassini’s epic Grand Finale plunge prior to its fiery death.

Cassini blasted off from Earth on October 15, 1997. After a near-seven-year journey, it arrived at its destination, some 93 million miles from home. Yet it wasn’t until April 2017 that it began its final descent into Saturn. The Grand Finale began on April 26, when the intrepid probe went where nothing from Earth had gone before, dramatically diving between the planet and its vast ring system a total of 22 times.

Using its dish-shaped antenna as a shield against potentially-damaging space particles Cassini plunged through the gap.

Shields Up! As we pass over #Saturn, we're turning our high-gain antenna into a shield RIGHT NOW to deflect oncoming ring particles. pic.twitter.com/kAxzY53uwT

— CassiniSaturn (@CassiniSaturn) April 26, 2017

As Cassini crossed Saturn’s ring plane it collected data using its Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument which is so sensitive it can detect the impact of minute dust particles touching off the spacecraft.

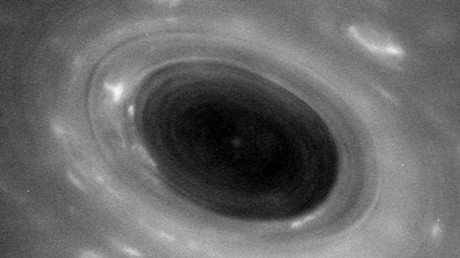

On April 27, NASA released stunning images of a giant hurricane on Saturn and the closest-ever photos of the planet’s atmosphere.

Then in early May, the space agency released an incredible movie of the probe’s first dive. It depicts the observations made as the spacecraft passed southward over Saturn on April 26.

The dive presented scientists with some interesting data, namely that the region appears to be relatively dust-free. It also marked the closest a spacecraft has ever been to Saturn. The footage shows Cassini’s journey, beginning with a swirling vortex at the planet’s north pole before moving past the outer boundary of the hexagon-shaped jet stream and beyond.

Cassini’s altitude above the clouds dropped from 45,000 to 4,200 miles (72,400 to 6,700km) as the movie frames were captured, decreasing the smallest resolvable features in the atmosphere from 5.4 miles (8.7km) per pixel to 0.5 miles (810 meters) per pixel.

But it wasn’t just images Cassini sent back, the spacecraft also beamed back an eerie empty recording of the space between Saturn’s rings. The recording, which was made on April 26, consists of mainly static with some erratic pings, signalling to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory that the area between Saturn’s rings consists of much less space dust than previously believed.

On May 7, Cassini’s two onboard cameras captured stunning images showing methane gas clouds swirling over the lakes and seas of the moon, Titan. The snap was taken from 316,000 miles (508,500km) above the moon’s surface. The dark regions in the images depict Titan’s hydrocarbon sea and smaller pockets of liquid methane.

Throughout the Grand Finale the probe continued to surprise scientists with new information. In July, with Cassini in it’s 15th of 22 orbits, data sent back caused scientists to rethink their understanding of magnetic fields after observations revealed that the one belonging to Saturn has no discernable tilt.

Until then scientists held the belief that for planets to generate magnetic fields, there must be a tilt between its rotation axis and its magnetic field axis. This was considered necessary to sustain currents flowing through the liquid metal deep inside the planets – which in Saturn's case is thought to be liquid metallic hydrogen.

Without the tilt, it was understood that the currents would eventually subside and the field would disappear (exposing the planet to a host of threats). This new finding from Cassini's magnetometer instrument is directly at odds with this theoretical analysis, however data indicated that Saturn’s magnetic field is surprisingly well-aligned with the planet’s rotation axis.

Surprising Saturn Science! @CassiniSaturn spacecraft finds the planet’s magnetic field has no tilt + more! Details: https://t.co/Mm8f0SKznBpic.twitter.com/RVGpPUGpwc

— NASA (@NASA) July 24, 2017

On August 14, Cassini entered its endgame when completing the first of five close flybys of Saturn and, in the process, becoming “the first Saturn atmospheric probe.” As it continued its terminal descent, at the end of August, it sent back information – this time revealing that Saturn’s rings may be far younger than previously thought.

On September 14, the day before its fiery death, NASA released some of Cassini’s final images. The spacecraft made its last mission photo at 12:58pm on Thursday September 14 – an observation of where the spacecraft would enter Saturn’s atmosphere.

Three days previously it captured a photo of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, named Goodbye Kiss, during its last, distant flyby.

Cassini began its final descent into the dark heart of the solar system’s second biggest planet on Friday, September 15. At about 07:55 EDT (11:55 GMT) the probe dove into the planet’s atmosphere, sending back information up until the last moment before eventually burning up in the atmosphere.

Look back in wonder: some of our final views of Saturn https://t.co/h01rZn8mvYpic.twitter.com/FXym30DUOy

— CassiniSaturn (@CassiniSaturn) September 15, 2017

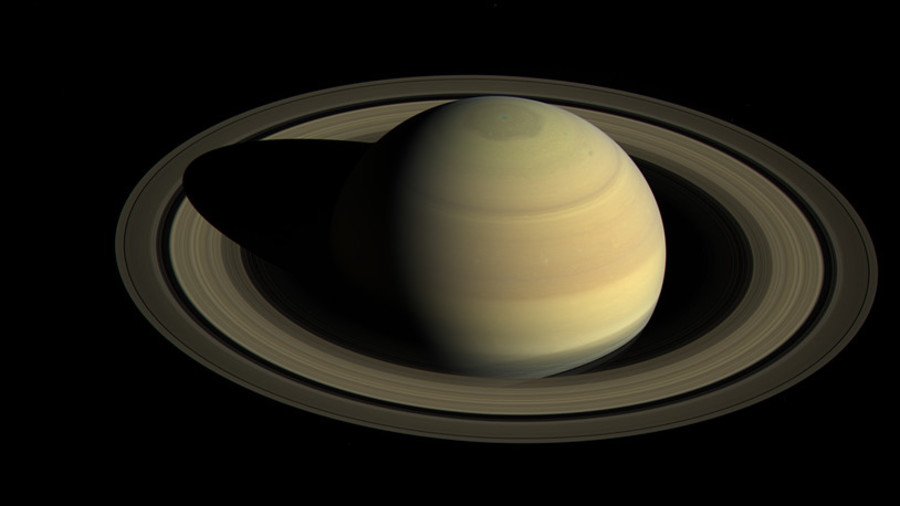

The gifts kept coming, however. On October 30, NASA released this amazing picture of Saturn’s northern hemisphere, taken by Cassini on April 25. The spacecraft had been waiting 13 years to catch Saturn’s north pole illuminated in all its glory – as it neared the summer solstice.

By the end of its life Cassini had observed almost half of a Saturn year, which is equivalent to 29 Earth years. The findings of the most distant planetary orbiter ever launched have revolutionized humans’ understanding of the eerily beautiful Saturnian system, and will continue to do so for years to come as scientists unpack more of the secrets learned by Cassini.

READ MORE: RIP Cassini: NASA’s $3.9bn space probe burns up entering Saturn (VIDEO)