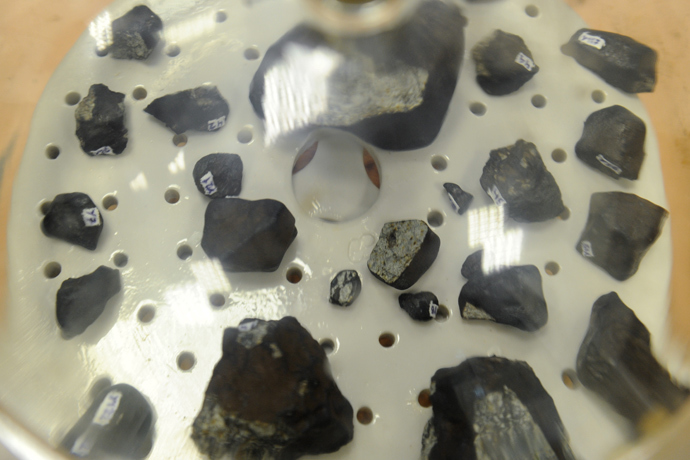

Chelyabinsk meteorite may have gang of siblings – study

The Chelyabinsk meteorite that hit Russia in February, injuring over a thousand, may have stemmed from a massive cluster of rocks which broke off from a disintegrating asteroid thousands of years ago, a new study claims.

Spanish astronomers have discovered that the Chelyabinsk bolide, an 18-meter wide 11,000-ton space rock that burst in a 460-kiloton explosion above Russia, used to be a part of a larger space body.

Scientists believe between 20,000 to 40,000 years ago, a massive body orbiting the sun broke up, most likely as a result of the temperature extremes and planetary gravitation it experienced while looping out past Mars and Venus.

Subsequently, the pieces of that asteroid formed a so-called

‘asteroid family’, a group of asteroids that share same

origin, composition and orbit. The parent of this potentially

hazardous asteroid family has been identified as 2011 EO40. Those

rocks are still flying somewhere in space, and just like the

Chelyabinsk meteorite, their orbits could intersect with that of

Earth.

In a new study, Carlos de la Fuente Marcos and his brother Raul from the Complutense University in Madrid said that they have found reliable statistical evidence for the existence of the Chelyabinsk cluster, or asteroid family.

The brothers used computer simulations of billions of possible asteroid orbits to find the ones most fitting into the Chelyabinsk impactor pre-collision orbit. They then searched the NASA database of known asteroids to find out if any of them follow those orbits. In the course of their investigation, they spotted the Chelyabinsk bolide family of about 20 asteroids, which range in size from 5 to 200 meters across.

“It appears to include multiple small asteroids and two relatively large members: 2007 BD7 and 2011 EO40. The most probable parent body for the Chelyabinsk superbolide is [asteroid] 2011 EO40,” according to their article, which is to be published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

The study points out that the shattered pieces of a rubble-pile asteroid can spread along the entire orbit of the parent body, making their collision with Earth possible on a time-scale of hundreds of years.

The Spaniards do admit that the orbits of the Chelyabinsk bolide

asteroid family have not been definitively calculated and there

is room for debate about whether they are a ‘family’ at

all. The Spanish researchers also said the gravitational pull of

the planets may affect the paths of the other rocks in the

cluster in a slightly different way, so even if the orbits of

these objects initially seem similar, they could radically change

down the line.

Still, Carlos de la Fuente Marcos warns, “More objects with the same orbital signature may encounter our planet in the future”.

With a diameter of some 200 meters, 2011 EO40 has already been

labeled a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) by the Minor

Planet Center (MPC). It was first classified as an Earth crosser

upon its discovery in 2011. So far its orbit has not been

entirely calculated, being modeled on a mere 34 days of

observations, whereas it usually takes years of follow-ups of a

space object to know its trajectory with certainty.

Jorge Zuluaga from the University of Antioquia in Colombia has doubts if 2011 EO40 is in fact the parent of the Chelyabinsk meteor and isn’t worried about it creating further impacts.

“I don’t think this particular asteroid is more hazardous than

others in the MPC list,” said Zuluaga, adding that the

asteroid isn’t on a direct collision course with Earth in any

case.

David Nesvorny from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder

Colorado was also skeptical of a definite link.

“It is not obvious to me why [the Chelyabinsk meteor] cannot be a fragment that was produced by a collision in the main asteroid belt, and evolved to its impact orbit by a few planetary encounters,” he told the journal Nature.

Further tests would be needed to confirm if 2011 EO40 was

Chelyabinsk’s parent rock. Sending a probe into space to bring

back samples is the only way to be completely sure. Another

cheaper and a less conclusive option would be to analyze the

light bouncing off it and collate its composition to fragments of

the meteorite that hit Russia.