Atomic mafia: Yakuza ‘cleans up’ Fukushima, neglects basic workers' rights

Homeless men employed cleaning up the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant, including those brought in by Japan's yakuza gangsters, were not aware of the health risks they were taking and say their bosses treated them like “disposable people.”

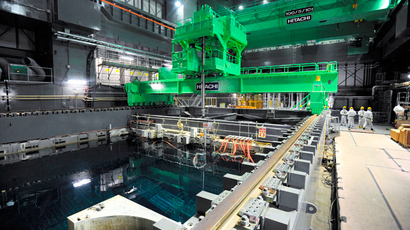

RT's Aleksey Yaroshevsky, reporting from the site of the world's

worst nuclear crisis since Chernobyl, met with a former Fukushima

worker who was engaged in the clean-up operation.

"We were given no insurance for health risks, no radiation

meters even. We were treated like nothing, like disposable people

– they promised things and then kicked us out when we received a

large radiation doze," the young man, who didn't identify

himself, told RT.

The former Fukushima worker explained that when a job offer at

Fukushima came up he was unemployed, and didn't hesitate to take

it. He is now planning to sue the firm that hired him.

"They promised a lot of money, even signed a long-term contract, but then suddenly terminated it, not even paying me a third of the promised sum," he said.

While some workers voluntarily agreed to take jobs on the nuclear

clean-up project, many others simply didn't have a choice.

An investigative journalist who went undercover at Fukushima,

filming with a camera hidden in his watch, says that many of the

workers were brought into the nuclear plant by Japan's organized

crime syndicates, the yakuza.

"In Japan, quite often when a certain construction project

requires an immediate workforce, in large numbers, bosses make a

phone call to the Yakuza. This was the case with Fukushima: the

government called Tepco to take urgent action, Tepco relayed it

to their subcontractors and they, eventually, as they had a

shortage of available workers, called the Yakuza for help,"

Tomohiko Suzuki told RT.

According to Japanese police, up to 50 yakuza gangs with 1,050

members currently operate in Fukushima prefecture. Although a

special task force to keep organized crime out of the nuclear

clean-up project has been set up, investigators say they need

first-hand reports from those forced to work by the yakuza to

crack down on the syndicates.

Earlier this year, Japanese police made their first arrest, detaining one yakuza over claims he sent workers to the crippled Fukushima plant without a license. Yoshinori Arai regularly took a cut of the workers' wages, pocketing $60,000 in over two years.

Meanwhile, according to Tepco's blueprint, dismantling the

Fukushima Daiichi plant will require at least 12,000 workers just

through 2015. But the company and its subcontractors are already

short of workers. As things stand now, there are just over 8,000

registered workers. According to government data, there are 25

percent more openings for jobs at Fukushima plant than

applicants. Tomohiko Suzuki says these gaps are often filled by

the homeless and the desperately unemployed – people who have

nothing to lose, including those with mental disabilities.

Due to the fact that the Japanese government has been reluctant

to invite multinational workers into the country, its nuclear

industry mostly uses cheap domestic labor, the so-called "nuclear

gypsies" - workers from the Sanya neighborhood of Tokyo and

Kamagasaki in Osaka, known for large numbers of homeless men.

"Working conditions in the nuclear industry have always been

bad," the deputy director of Osaka's Hannan Chuo Hospital,

Saburo Murata, told Reuters. "Problems with money, outsourced

recruitment, lack of proper health insurance – these have existed

for decades."

The problem is that after Japan's parliament approved a bill to fund decontamination work in August 2011, the law did not apply existing rules regulating the profitable construction industry. Therefore, contractors engaged in decontamination were not required to share information on their management, so anyone could instantly become a nuclear contractor, as if by magic.

It is now emerging that many of the cleanup workers, including

those recruited to work at the power plant by the yakuza – mostly

with gambling debts to the organization or family obligations –

often had no idea what they were dealing with.

"They were given very general information about radiation and

most were not even given radiation meters,” Tomohiko Suzuki

told RT. “They could have exposed themselves to large doses

without even knowing it. Even the so-called Fukushima 50 – the

first group of workers sent there immediately after the disaster

– at least three of them were recruited by the yakuza."

Suzuki published details of what he says is solid evidence, but

Tokyo Electric Power Company officials strenuously deny that any

mistreatment or organized crime involvement is taking place.

"We are doing everything to ensure that our workers operate in

safe conditions. We also deal harshly with law-violating

subcontractors," TEPCO spokesman Yoshimi Hitosug said.

There are no exact figures on how many people have worked on the

Fukushima cleanup operation. Rough estimates suggest that this

may be up to a quarter of a million people. With experts saying

it may take another 40 years to completely liquidate the

aftermath of the disaster, the lives of millions could be

affected.