Guantanamo hunger strike hits 6-month mark

A hunger strike that started over a routine cell search and escalated into a worldwide debate on the future of Guantanamo continues. For some, it may have expedited a release, but to others, it has brought only humiliation.

RT's GITMO hunger strike timeline

At its peak more than two-thirds of Guantanamo’s 166 prisoners

refused food. More than 60 continue the strike at this time.

It began in February when several prisoners accused guards at

Camp Delta of confiscating their books, letters and other

personal possessions, as well as restricting their activities,

for no obvious reasons. Several inmates also said that US

officers mishandled the Koran.

But as time went by the strike numbers swelled, it became a

protest at the ongoing existence of a prison in which more than

half of the inmates have been cleared for release.

Even General John Kelly, who oversees the facility on Cuba’s

south coast, has admitted that when ‘frustrated’ prisoners have

no hope of freedom or even a trial (only 9 of those inside have

faced charges), there is little for them to lose.

Despite US President Barack Obama’s repeated public opposition to Guantanamo, by the time the strike began, the chances for a legal resolution for any inmate were smaller than ever. For many of the prisoners, the US had deemed it unsafe to return them to their own countries, others were considered dangerous, but the evidence against them was either insufficient or obtained through torture and inadmissible in court (even if the torture had been performed by US allies in the first place).

With each passing year of the Obama administration, Congress made

it more difficult for the president to find a compromise. By

2013, the US defense secretary had to personally guarantee that

each inmate would not commit any future crimes against the

country, and territories where recidivism attacks had taken place

were not eligible altogether – even in cases where the prisoners

themselves had been ruled innocent.

As prisoners began to collapse from low blood sugar, US officers

ordered for them to be force fed, a practice that the UN Human

Rights Commission has classified as ‘torture’, and which has been

forbidden by the World Medical Association.

At one point during the strike, over 40 of the inmates were

subjected to the practice.

During the once-a-day ‘meal’, captives, whom the US classifies as

prisoners of war, are strapped into a chair, a tube is pushed

into a nostril, and then a mainly protein-based solution is

pumped into the digestive tract.

The UN’s chief rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, spoke to RT on

several occasions, and in his latest interview on Monday, he

continued to say he has still not been granted the kind of access

that would facilitate an in-depth investigation of prison

practices. This included not being given access into certain

areas, as well as the privilege of interviewing an inmate of his

choosing privately – both of which are key to the work Mendez

does as inspector.

“The terms of visits to detention centers that I apply have

been approved by the Human Rights Council. So I’m not asking the

United States to give me preferential treatment, but I can’t give

them preferential treatment either.”

A newly appointed envoy to oversee Guantanamo looks like a

commitment to take the issue seriously, says Mendez. But he also

noted that the Pentagon official, who for years has been in

charge of Guantanamo on issues of detention, has admitted after

resignation that the facility needs to be closed. Both are signs

of a move toward progress, according to Mendez.

Accusations of misconduct, however, have continued to pour into the media – the most notable recent allegation having to do with sexual abuse and harassment.

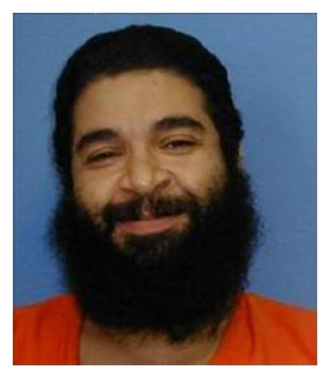

Shaker Aamer, the last British resident imprisoned in Guantanamo

Bay, says he suffers from regular assaults, including those of a

sexual nature, from the guards. He has spent more than 11 years

there without charge.

Yet Aamer’s lawyer Clive Stafford Smith told RT that his client

will most likely be sent to Saudi Arabia by the US, because in

Britain he is a crucial witness in a criminal investigation that

authorities would allegedly like to disappear.

The overwhelmingly anti-US coverage of the strike from media

around the world, has spurred the US administration into belated

action. Obama has stepped up calls for Congress to follow his

lead in closing the facility.

Gitmo prisoner support groups have criticized successive British

governments for not doing enough to free Aamer. The latest wave

of calls for his release came over concerns that the US was

seeking ways to render him to Saudi Arabia, a move that he has

pledged to resist “every step of the way.”

Another strong criticism leveled at the prison recently came from

Senator Dianne Feinstein, chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence

Committee, who called operating the prison “a massive waste of

money.”

"Ten years with no hope, no trial [and] no charge,” for

those inmates, Sen. Feinstein said.

The chairwoman also slammed the Obama administration for

permitting prison officials to force-feed detainees, saying "I

believe it violates international norms and medical ethics, and

at Guantanamo it happens day after day.”

Now in addition to human rights error and the ongoing urging of

President Obama, the escalating cost of keeping dozens of men

locked up indefinitely could finally prompt that sort of

response, especially during an era of sequestering that has

stripped the Pentagon of much of its funding this year already.

A little more than a week ago, an analysis, first provided to

Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and made public last week,

concluded that the cost of keeping the Pentagon open will amount

to $5.242 billion by the end of 2014.

Despite this, the Republicans maintain that any plans for release

are putting American lives at risk. Republican reasoning is that

the inmates wish America ill, and since they were caught on the

battlefield, Guantanamo is exactly where they should stay.