Gaza’s night guard: Stalking with Qassam fighters

Every night several dozen teams from the military wing of Hamas patrol various parts of the Gaza strip. Founded in 1992, the Izz ad-Din Qassam Brigades made their objective to fight ‘the occupier’ Israel.

Becoming a member of the group is considered a great honor among

Palestinians. RT observer Nadezhda Kevorkova toured the volunteers’

Gaza outposts and spoke to the fighters and their leaders.

Qassam Brigades by night and day

Several cars await us at the meeting point, five men in each. We

start off and ride through residential neighborhoods, passing by

checkpoints that you don’t get to see there during the day. At some

point, we pass from a paved road to rough terrain. It’s pitch dark

and the violent wind carries the rain sideways as we stop at an

obscure structure that looks like a fence with a shed.

A group of about 15 men emerge at the side of the road, all of them armed with automatic rifles and wearing fatigues, their faces covered. They look like thoroughly-trained fighters, tall and strongly built, with those ‘crouching tiger’ moves that look straight out of spec ops action movies.

The men greet us, forming a semicircle. Their leader is a lean, sinewy man with a beard, who doesn’t cover his face.

He briefs us on his team’s structure and manning principles, and

goes on to tell us all of his men were there defending Gaza against

the IDF’s Cast Lead offensive in 2008. They also fought in the most

recent eight-day campaign last November.

The Qassam Brigades fire their own rockets on Israel whenever the IDF attempts a crackdown on the Palestinians. The rest of the time, the Brigades abide by the ceasefire announced by Hamas.

The fighters let us take pictures of their mortar and its shell,

and display their unsophisticated small arms. Some agree to pose

for pictures themselves, but the rain and the darkness ruin all of

our attempts at footage.

The Brigades have their own strongholds, gun stores and training

grounds – all located in the Gaza Strip. The group’s cells in the

West Bank were destroyed during the Second Intifada of 2000.

Currently, any training in the open there is out of the question,

and most Brigades’ cadres have to stay deep undercover.

‘Us against them’

The next team we visit rather seems to be composed of raw recruits and teenagers. They stand a head shorter than the men in the previous unit. The youngest of them is 17, although the group also has a few men aged above 30. They all look like obvious amateurs, as yet untrained to move like a single organism, the way the previous squad does.

The team is taking shelter from the pouring rain under a makeshift shed. Their leader tells us all of his volunteers are regular folk, married men with daytime jobs, or students. These nightly patrols are something they have signed up for themselves, with no paycheck attached. But once you are on the team, the nightly vigil becomes a commitment that cannot be skipped for whatever reason, be it work, bad weather of family matters.

Finally, the team leader offers to take us to his unit’s headquarters, located a few kilometers away from the Israeli border. The place serves as both the group’s training ground and an observation post for tracking enemy activity in the area.

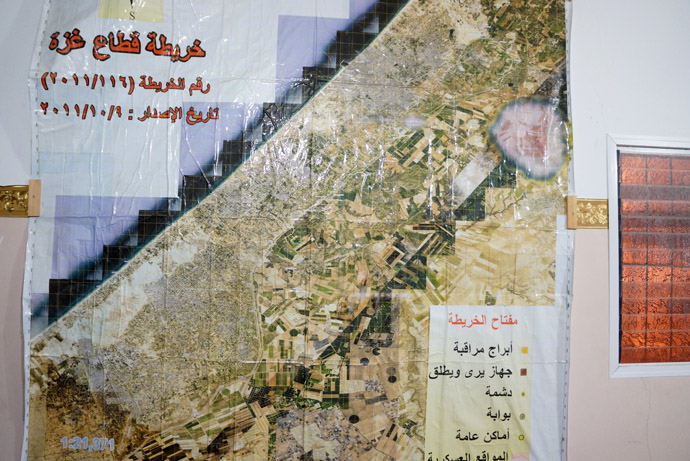

The HQ is a single room with a few tables and chairs, and a secluded corner where you can sit back or deliver a prayer. The room displays a topographic map of Gaza and the surrounding area. The strip itself is marked as densely-populated, with hardly a spot still vacant, whereas outside of its stretch fields of empty land.

The team leader points to them, saying, “This is our land, occupied.”

A stairway leads from the courtyard to a rooftop, which serves as an observation post. From up there, you get a view of Palestinian houses, freshly rebuilt from the debris left by the war of 2008. Entire neighborhoods lie in darkness in Gaza, while further out, Israeli territory gleams with electric light. We are about 2km away from the border.

The fighting of November 2012 was the first instance when rockets fired from Gaza actually reached Tel Aviv. Observers are engaged in an endless debate over whether those rockets had been manufactured in Gaza or smuggled from abroad.

The headquarters is located as far from the nearby houses as possible in a place as crammed as Gaza. It is surrounded by a garden of sorts, with a path winding its way through grapevines. The cabin’s walls are pockmarked with shells and bullets from earlier fighting. The site is guarded by a few veteran fighters.

The team leader wears no mask. He tells us the Brigade numbers about 4,000 volunteers at the moment. This doesn’t include a reserve composed of the maimed and the wounded, who are still considered to be Qassam fighters.

Israel estimates the Brigades’ strength at 40,000 men, which seems totally unrealistic given the meager size of the Palestinian territories.

The Brigades face an enemy armed with sophisticated military hardware and technology: jets, drones, tanks, missiles, and surveillance systems. Against that, the volunteers have themselves and their families, who support them.

“We have no army,” the team leader tells me. “We have no jets and no tanks. All we have is volunteers. None of the fighters or commanders get any pay. My wife sells her jewelry to buy me ammo and a uniform.”

Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, founder and Spiritual Leader of Hamas, once issued a fatwah that qualified suicide attacks on the Israelis as a legitimate “delivery means” that Palestinians are forced to resort to by virtue of having no armed forces and no traditional defense capabilities.

“We don’t seek death,” says the team leader – “We are ready for it. Our advantage is not in our strength, but in the fact that they like life, and we like death. But we are not here to die; we are here to fight.”

Like most Palestinians, the team leader avoids words like ‘Israel’ or ‘the Israelis’: for these people, it’s ‘us against them’.

The Brigades claim to have killed a total of 1,365 Israelis and wounded 6,411 in their twenty years of operation. The estimates include kills scored during terrorist attacks as well as during the more classic military engagements by Qassam fighters.

Israel gives a more conservative assessment of the Brigades’ body count, and describes any activity by Hamas or its military wing as “terrorist.”

The Brigades have abducted dozens of IDF personnel over the years, but the only one to survive captivity has been Gilad Shalit. It is Israel’s tactic to tag each of its servicemen with an RFID chip attached to their uniform, and track them down and deliver an airstrike on the source in case of capture, so as not to be forced to bargain and exchange prisoners with the Palestinians.

'United we stand'

The fighter explains the Brigades’ structure for us:

“Our commander is a single man who is in charge of all the

activities. We have six squads and four tiers of subordination. All

of our actions are coordinated: we attack as one, stand our ground

as one, or fall back as one.”

He outlines a small sector on the map:

“This is our area of responsibility. We keep up round-the-clock surveillance here.”

A night watch is also training time for the volunteers. Each of them has to report to a specially-designated position once a week and keep watch from 11pm through 4am.

The Qassam Brigades have been awash with new volunteers ever since the latest fighting last November, when the militia’s mortar teams managed to score several hits on Tel Aviv.

“Now everyone wants to be part of us,” the leader says. “We have fresh volunteers coming all the time: students, policemen, sharia scholars, engineers, blacksmiths, merchants and teachers.”

Not just anyone can join, however. Each candidate has to pass a

test and prove he is capable of being a fighter. Not all volunteers

stay in the ranks for long, either: some eventually quit due to ill

health, others drop out because of the stress. But if a volunteer

is ever wounded in action, he becomes a veteran and gets to receive

assistance from Hamas, which is extended to family members as well.

Veterans are granted preferences to enroll in Palestinian

universities. The Islamic University of Gaza employs some 400

disabled vets, who occupy a block of their own on the campus,

making all sorts of household articles, from furniture to works of

art. Almost all the furniture in Gaza comes from that

workshop.

“We have ranks, which are assigned based on a person’s skills and capacity,” the leader continues. He actually appears to be younger than some of the men in his team.

“Just being acquainted with a Brigades member can get you jailed for 25 years,” a Palestinian named Mohammed tells me. His own brother was arrested in the West Bank on suspicion of having ties to the Brigades. Sentenced to 25 years in prison, he eventually spent nine years behind bars until he was released as part of the Gilad Shalit prisoner exchange.

“If they find out you know some of the volunteers, they may seize you, lock you up for years without a trial, and torture you to break your will and force you to cooperate. These people here are taking a great risk in coming to meet with you.”

The next day after my visit with the Brigades, I happened to bump into some of the volunteers in the streets of Gaza. They gave no hint of recognition. One of the nighttime fighters was a humble caretaker sweeping a schoolyard. Another one was a baggily clad, weak-sighted school teacher squinting into a class book.

Nadezhda Kevorkova, Gaza, RT