Back to the Future: Solving the Kurdish issue, Turkey 2023

The so-called Kurdish issue has been a thorn in Turkey’s side since the PKK launched its terrorist struggle against the Turkish government in 1984.

Turkey’s current government, led by the Justice and Development Party (AK Party or AKP), however, has vowed to bring a peaceful resolution to the conflict and has to this end launched its ‘Kurdish overture’ in 2009.

The overture’s preparatory moves have now come to some kind of fruition and to prove the point, the ever-popular yet equally divisive PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on November 16, flew to the southeastern city of Diyarbakır to conduct some meaningful meetings. Once on the ground, Erdoğan first visited the offices of the Metropolitan Authority of Diyarbakır, meeting Mayor Osman Baydemir, as well as the independent members of parliament Ahmet Türk and Leyla Zana, two important names in the Kurdish political landscape of Turkey. This half-hour visit was followed by the PM going to the governor’s office.

This orchestrated tour of Diyarbakır’s government buildings carried some extraordinary weight. While Tayyip Erdoğan was in the air, the President of the Kurdistan Regional Government (or KRG) in Northern Iraq, Massoud Barzani, took the land route from Erbil in time to meet the governor M. Cahit Kıraç and Tayyip Erdoğan in the offices of Diyarbakır’s Governor’s Office. Later on Erdoğan, accompanied by his Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, met with Barzani for face-to-face meetings at the Green Park Hotel, where the KRG President was staying.

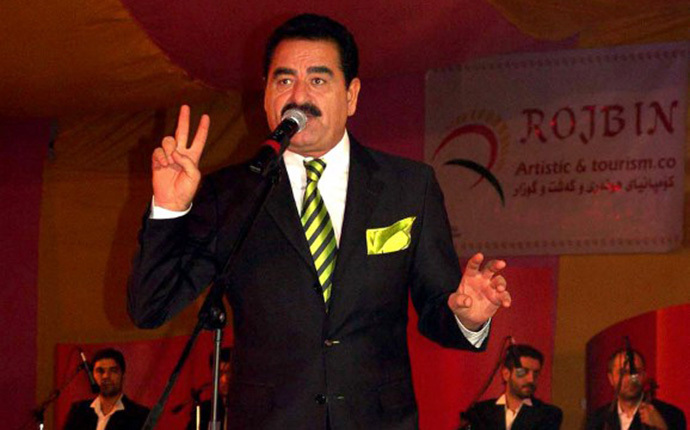

On the sidelines of these high-level meetings, other important get-togethers took place as well. In Barzani’s retinue the popular Kurdish singer Shivan Parwar, originally hailing from Turkey, also came to Diyarbakır. Living and working in exile since 1976, Parwar, met the incredibly popular Turkish singer of Kurdish descent İbrahim Tatlıses. Together these two cultural icons performed duets singing in front of large crowds including Tayyip Erdoğan and Massoud Barzani as well as various top members of Turkey’s government.

Tatlıses addressed the crowd in Turkish as well as Kurdish, stating that the day stood out as a feast day of peace and stressing that there is no difference between a Laz, a Circassian, an Arab, a Kurd and a Turk.

Those words may very well give many Turks, particularly those opposed to Erdoğan and his AKP-led government, pause to think as, to their mind, sentiments like these could destroy the glue of Turkish nationalism holding together the country and its people.

Even though the republic has always been at pains to stress that Turkey is a unitary nation state with a homogeneous population, the reality is that Turkey’s population is ethnically diverse and an heterogeneous amalgam of individuals. Anatolia has always been home to a wide variety of ethnic and religious groups and sub-groups, and today, the makeup Turkey’s population is the result of Ottoman government policies carried out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These policies were aimed at transforming Anatolia (the heartland of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic’s geo-body, using Thongchai Winichakul’s coinage denoting the territory of a nation as expressed on a map and inscribed on the people’s consciousness) into a Muslim homeland where refugees from the Russian Empire and the Balkans were settled.

In the early 20th century, Anatolia was thus home to ethnically heterogeneous Muslim groups: in addition to a large majority of Turkish Muslims, there were Kurds, Arabs, Lazes, Muslim Georgians, Greek-speaking Muslims, Albanians, Macedonian Muslims, Pomaks, Serbian Muslims, Bosnian Muslims, Tatars, Circassians, Abkhazians and Dagestanis among others. Prior to the formulation of Turkish nationalism as an ideological binding-force, the diverse ethnic groups in Anatolia were united by their common identity as Muslims and their allegiance to the Ottoman Caliphate, abolished in 1924.

Earlier I put forward that the idea of the Anatolian population as a Turkish entity was first proposed as early as 1922, the year prior to the official proclamation of the republic. And in 1924, the first Turkish constitution proclaimed that the “name Turk, as a political term, shall be understood to include all citizens of the Turkish Republic, without distinction of, or reference to, race or religion.”

A policy of ‘Turkification’ carried out in the first decades of the republican existence has meant that these various ethnic subgroups have in time merged with the Turkish mainstream.

In the late 20th century then, awareness of the Turkish population’s ethnic diversity became current again. Opponents of Erdoğan and the AKP now fear that the government’s long-term goal (as arguably expressed in the AKP’s policy statement Hedef 2023) is to transform the nation state Turkey into an Anatolian federation of Muslim ethnicities, possibly linked to a revived caliphate. In this way, Turkey’s future (as a nation state) would arguably become subject to Anatolia’s past as a home to many different Muslims of divergent ethnic background.

The fact that Erdoğan’s oft-repeated reference point is the first assembly of what was to become Turkey’s parliament on 23 April, 1920, seems to render strength to such contentions. The first assembly consisted of representatives of Anatolia’s Muslim population, the then-Kemalist constituency, who had pledged allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph, Mehmed VI – two years later, the transformation of Anatolia’s Muslims into Anatolian Turks begun in earnest.

Is it sheer coincidence that Turkey’s PM is now basing his policy decisions on the shape of Anatolia’s early 20th-century population? Will solving the Kurdish issue eventually lead to a revived sense of Islamic solidarity among Turkey’s population? This then also leads one to wonder what Turkey will look like on the occasion of the republic’s centenary in 2023: will it be a nation state with a fully democratic society, as claimed by Tayyip Erdoğan, or will it be an amalgam of nations united by their adherence to a revived Islamic caliphate, as feared by his opponents?

Can Erimtan for RT

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.