Saints, dog dictatorship and supercops from St. Petersburg: 600 years of Russian comics

Although the United States cannot be called the birthplace of comics, it is largely where the genre realized its commercial potential, becoming a big business and achieving mass popularity. On September 25, Americans celebrate National Comic Book Day. While the holiday is purely American, it should come as no surprise that fans of the genre across the world also celebrate it. And Russia is not an exception.

Russian comics cannot yet compete with either their Western or Eastern competitors from a commercial point of view, but their history is no less rich.

RT recounts how tales with pictures appeared in Russia and how this genre operates today.

Forward to the past

The roots of self-expression by telling stories in pictures can be traced back a thousand years. However, there is no clear understanding of when narrative illustrations with captions turned into what we today call comics.

In Russia, the genre is by no means young, although the exact release date of the first comic in Russia hasn’t yet been pinpointed, as it has in the US. This is due to the already mentioned lack of agreement on what to consider a comic book. It must be kept in mind that, apart from the visual aspects, comics are primarily a literary genre. It’s not enough to simply draw a story in pictures. Dialogue and a narrative must accompany it.

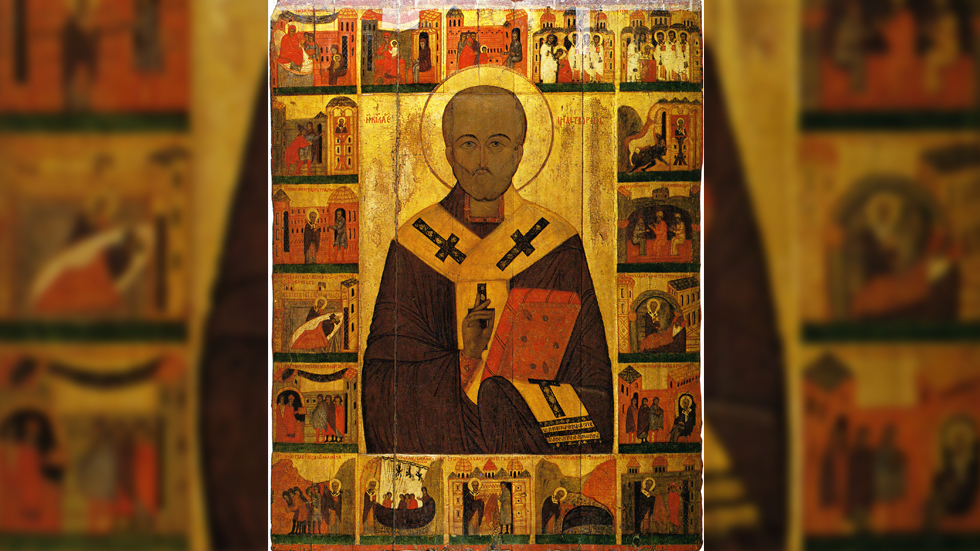

Following this logic to study the genre's history takes us all the way back to Russian iconography. As early as the 13th century, the first hagiographic icons appeared. Such icons depicted the lives of saints in the Orthodox Church. At the center was a large image of the saint, and along the perimeter were illustrations of episodes from his life, with a descriptive text essentially accompanying each one. Furthermore, and more importantly, the illustrations were arranged in chronological order. Thus, parishioners could easily and quickly become acquainted with the biographies of the saints.

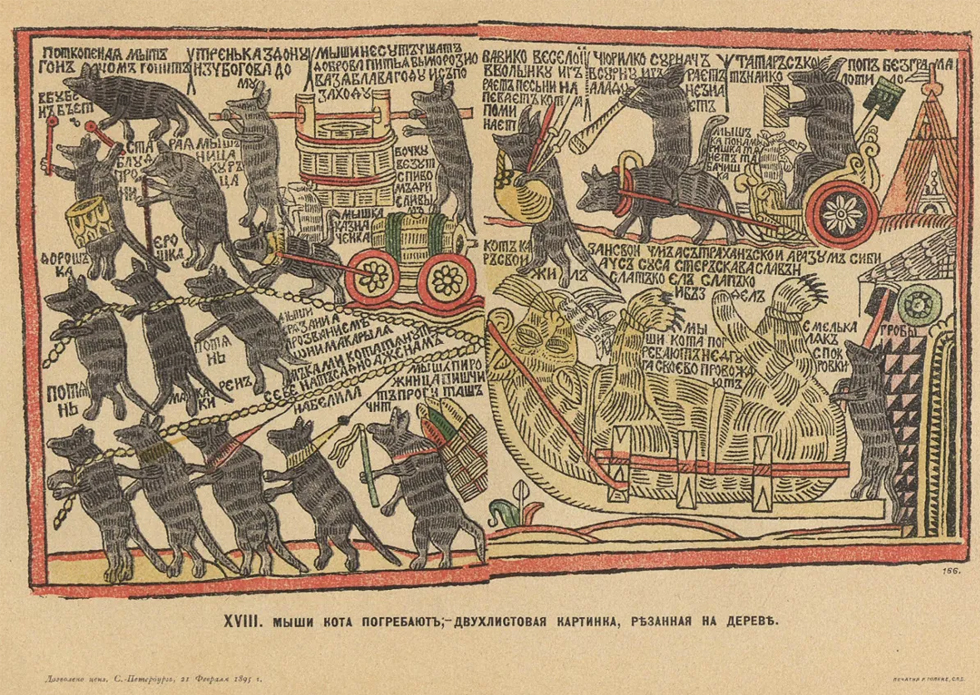

Another predecessor of comics is what is called lubok. This is a graphic image, often a caricature of some sort, of an episode accompanied by an explanatory text. This light and mass genre originated in China two millennia ago and appeared in Europe in the 15th century. A distinctive feature of the medieval lubok was its accessibility to the broad and mostly illiterate masses.

Lubok began to actively develop in Russia in the 17th century when book printing in the country had already reached an industrial scale. As a consequence, many printing houses began to publish lubok. This allowed the genre to gain popularity not only within the aristocracy but among a wider swath of society.

While religious subjects were predominant in the early Russian lubok, the genre gradually began to expand, and over time, those depicting fairytales or festivities, or on philosophical topics began appearing. There were even legal leaflets.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the authors of lubok began to create more complicated plots and in some cases borrow them from famous European writers. For that reason, one could see extracts from the works of Johann Goethe, François-René Chateaubriand, and Anna Radcliffe. Gradually, original stories emerged, many of which offered a moral lesson, admonishing about the dangers of drunkenness, greed, and other vices.

As printing developed further, lubok did as well. Entire factories were equipped with dozens of machines to meet readers' needs. According to the encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron, in 1893, the number of copies of lubok had increased to 4.5 million. The most popular genres were literary (about 2 million prints), followed by religious and moral (about 1.5 million).

The largest publisher was Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin, a leading entrepreneur of that time. He also printed large quantities of famous lubok stories, themed calendars, and paintings. Sytin paid particular attention to Russian literature and published many short stories and novellas by Alexander Pushkin, dramas by Alexander Ostrovsky, as well as stories by Mikhail Lermontov in the form of lubok. He also published the portraits of Russian writers with scenes from their works.

The genre of caricature was closely intertwined with lubok. Although biting satirical illustrations on hot topics were censored in tsarist Russia, they never stopped being published. There were many underground publishing houses, which were given unofficial support by major entrepreneurs. Caricatures played a vital role in the history of comics because the well-known ‘bubble’, containing the speech of the characters, appeared in this genre.

The first Russian comics

Works resembling the modern conception of comics appeared in the middle of the 19th century. Many of them were printed in newspapers and occupied a large number of pages, while others were published separately. Here you can already find almost all of the characteristics that we associate with comics: a concise but complete story divided into chapters, character development, intricate plots, and, of course, captions for the drawings that provide either narration or the speech of the characters.

The newspaper department of the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg recently published a complete comic book called ‘Mr. Forget-Me-Not's Voyage to Pyatigorsk. His Treatment, Adventures, Impressions, and Disappointments’, which had been first published in the newspaper ‘Illustration’ in 1858, while in 1875 it was released as a separate edition — 17 years before September 25, 1892, when the first American comic book, ‘Bear Cubs and the Tiger’, appeared.

The drawing itself stands out first and foremost for not only depicting the events but being replete with visual humor. Fantastic creatures appear on some pages. The only thing missing is the usual bubbles – all the text is printed at the bottom of the picture.

Comics continued to develop in tsarist Russia, where they followed the lubok tradition. Then, at the turn of the 20th century, the children's magazine ‘Zadushevnoye Slovo’ became popular. This is where the first full-fledged comics were printed in Russian – mainly translated from French.

Сomics and cartoons by Ivan Simakov began to appear in the famous satirical daily ‘Budilnik’ at the beginning of the 20th century. The writers Anton Chekhov, Vladimir Gilyarovsky and Aleksey Budischev were also published in this magazine. After the Russian Revolution, Simakov worked at the well-known ROSTA Windows {which produced the Soviet agitprop posters that are famous for their distinctive style – RT}, while the magazine ‘Satyricon’ released comics and cartoons by the artist Aleksey Radakov. In Soviet times, he collaborated with the magazines ‘Crocodile’ and ‘Begemot’ and illustrated children's books.

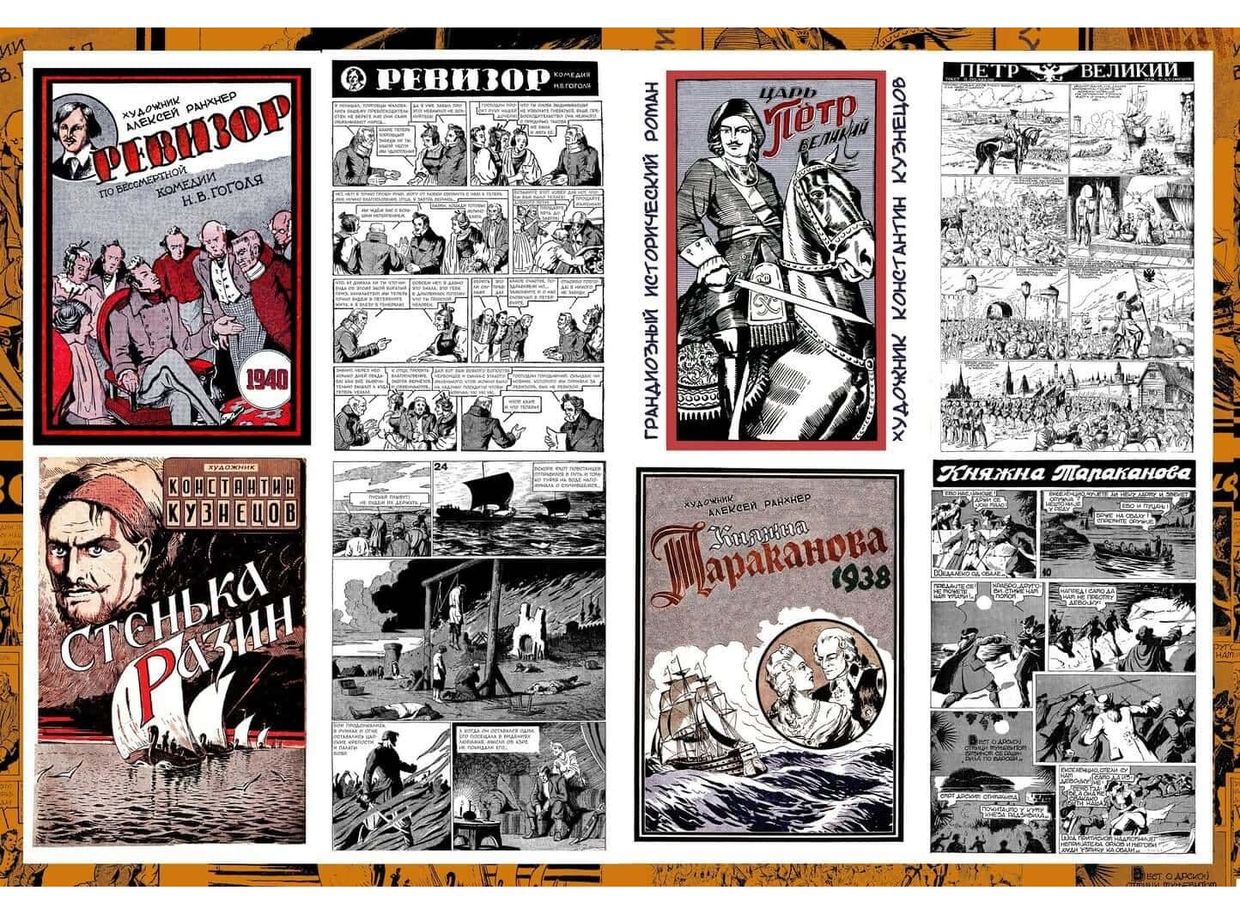

After the Revolution, the comic book genre left the country along with much of the Russian intelligentsia, but it lived on abroad. In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the 1930s and 1940s, Russian comics experienced their golden age.

A large colony of Russian emigres settled there, giving the world many comics on Russian topics that were published throughout Europe. Everyone read Russian comics except those in Russia itself. These classic works have recently found their way to their homeland and are now finally being reprinted by minor publishing houses.

Comics in the USSR

In the Soviet Union, the genre’s development came to a stop. Those prerequisites for the industry to develop commercially that had emerged before the Revolution remained only prerequisites. No publishers in the socialist country were ready to deal with what was seen as a bourgeois genre. Comics appeared mainly in kids’ magazines and journals for schoolchildren and teenagers. Nevertheless, the genre thrived within these seemingly narrow confines.

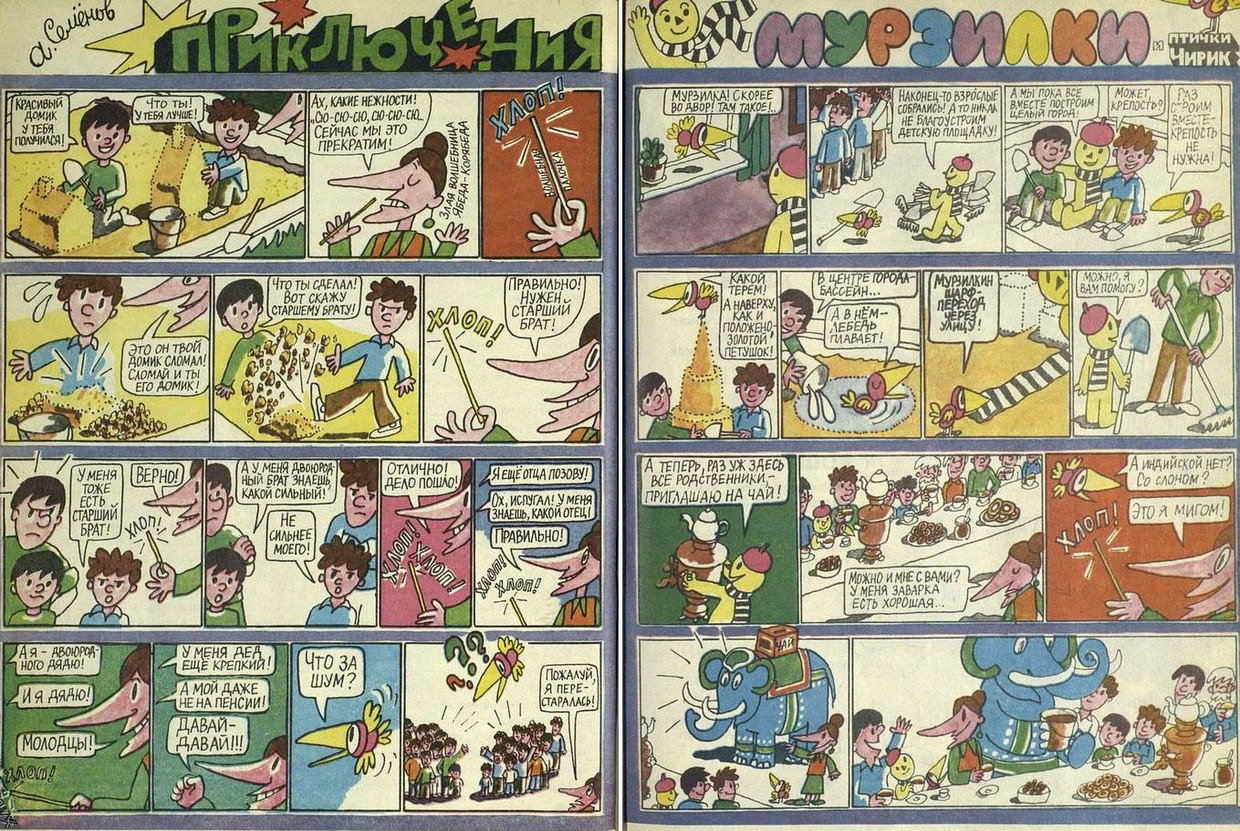

Perhaps the most famous comic book character of the Soviet era is Murzilka. A children's magazine of the same name appeared in 1924. In 1937, the image of the popular yellow man in a red beret was created. Before the Second World War, comics about Murzilka regularly appeared on the magazine's pages in almost every issue. During the war and in the first decade after, illustrated stories disappeared from the publication, but in 1959 Murzilka returned to the pages of the magazine and increasingly became a comic book hero.

Works of this genre were published in children's or humorous journals such as ‘Ezh’, ‘Smekhach’, ‘Begemot’, ‘Chizh’, ‘Veseliye Kartinky’, and ‘Pionerskaya Pravda’. Some of the publications were regular, while others were only occasional.

In the mid-1980s, comics in the country began to develop rapidly, and the genre stopped being perceived as purely for children. There was even a series that was traditional for the genre about a sailor called Koshkin by Boris Tsygankov, which follows one main character.

Perestroika ushered in a boom in comics. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, interest in Western pop culture increased, and the first American comics appeared in Russia. These were mainly translations of Disney comics about the studio's famous cartoon characters. Second, many domestic authors appeared who sought to launch their own series. Many tried to combine the aesthetics of American comics with a Russian flavor, although very few achieved success with this.

A considerable number of publishing houses also appeared, often surviving for only a few years. Demand for domestic authors had not yet coalesced, and people wanted to read Western comics.

From the ‘90s to the present day

Nothing changed significantly in the 1990s. More and more foreign comics hit the market, but among local authors only children’s comics were published widely. Moreover, it was more profitable to publish Western comic books than to promote Russian writers and artists since the characters were more recognizable. Buying licenses for old foreign comics was significantly cheaper than ordering an original work.

Of course a lot has changed since the 1990s. First of all, not everybody actually bought the licenses honestly, while comics were in any case still a niche genre.

Nevertheless, the new century saw a number of changes. Large publishing houses became interested in Western comics, and the popularity of Western superheroes has grown tremendously. Hollywood, which has been adapting comics for the screen for the last 20 years, played an essential role in this. Also, Japanese manga gained immensely in popularity and began being licensed and published in considerable numbers.

The last ten years have seen something of a revival of Russian comics and a blossoming of the industry in general. New authors, new ideas, and new technologies have appeared, while specialized shops have opened. You can now read ‘Spider-Man’ and ‘Batman’, as well as ‘Death Note’ and ‘Attack on Titan’ in Russian.

There was also a breakthrough in the Russian segment. The publisher Bubble Comics is the most noteworthy, having become the country's largest publisher of original comics. Bubble has been on everyone's lips over the last couple of years in connection with the film adaptation of the ‘Major Grom’ series. The publishing house has already acquired a significant fan base over the ten years of its existence. The premiere of the film ‘Major Grom: The Plague Doctor’ reached a wide audience.

The film has been a success, and production has already been announced for another film – ‘Major Grom: Difficult Childhood’ – as well as the serial ‘Fury’, which is based on another Bubble series called ‘Red Fury’.

Bubble Comics was able to realize the dream of many Russian authors in the early 90s – writI guess superhero comics in a Western style, but with Russian characters. At the same time, the works cannot be called derivative in any way since, despite the American aesthetics of the drawings, the characters are thought out to the smallest detail and have a Russian flair. In addition, the authors have adopted what is called the ‘crossover’, a favorite technique of Marvel and DC.

Bubble is the Russian analogue of Marvel and DC – a large publishing house with its own universe, expensive production, and a sizeable number of authors. Meanwhile, independent comics are also developing in the country. Young authors who create their own content have appeared. They are self-publishing and many have earned an appreciative audience. Moreover, as in the rest of the world, independent authors are moving away from superheroes and are broaching more pressing topics and issues.

St. Petersburg native Vitaly Terletsky, who achieved a breakthrough with the book ‘Roman, the Winner of Swallows’ in 2018, has earned accolades. Two years later he released the sharp political satire ‘Sobakistan.’ In addition, Terletsky also does fan stories. For example, he writes a series about the adventures of JoJo (the most popular manga series) navigating the realities of Russia.

In 2019, Olga Lavrentyeva released the graphic novel ‘Survilo’, in which she told the story of her grandmother, who first survived repressions and then the blockade of Leningrad.

Meanwhile, the popularity of Japanese manga continued to grow, and Russian authors also began to work in this genre. The year 2014 saw the release of ‘The Legend of the Silver Dragon’ by Vladislav Yartsev, while in 2017 Bubble released its manga ‘Tagar’.