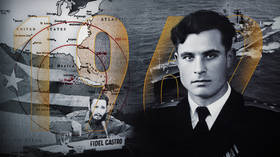

Dead Hand’s nuclear revenge: What would happen if the West launched an attack on Russia?

Imagine if one day we suddenly get a news alert to say the button’s been pushed and nuclear war has been unleashed?

Within hours, millions would be dead and hundreds of millions more would die in the following days. Gray ashes would soar into the air and scatter upon the ruins of what used to be Moscow. The US would have blown up all the ‘decision-making’ centers in today’s Russia. But what about Washington? The very same thing, but not only just the American capital – other key NATO cities would probably be destroyed as well.

That's the horrific reality for mankind if atomic weapons are ever used. Because, as modern Russian leaders often point out – there can be no winners in such a conflict.

Recently, the US army's former European commander, Ben Hodges, warned that his country would retaliate with "a devastating strike" against Russia if Moscow used its nuclear capability in Ukraine. Hodges, now a lobbyist at CEPA (a pressure group funded by US arms makers to promote, and maintain, NATO expansion in Europe) said Washington could target the Black Sea Fleet or destroy Russian bases in Crimea.

Living dead in charge of a superpower

In 1984, Konstantin Chernenko, a 72-year-old party worker and former head of Leonid Brezhnev's apparatus, sick with end-stage emphysema, became the leader of the Soviet Union. Ironically, given today's events, one was Ukrainian from Ukraine and the other a Russian-born ethnic Ukrainian.

“The leader of a great power turned out to be not just a physically weak, but a seriously ill person, actually a disabled person,” his successor, Mikhail Gorbachev, wrote in one of his books. Anatoly Chernyaev, who served at the time as deputy head of the International Department of the Central Committee, recalled that, when Chernenko was supposed to meet with the King of Spain, his assistants prepared pieces of his speech on small paper cards. “But Chernenko couldn't even read a piece of paper, he stuttered, not understanding a thing he was reading.”

Four years prior to his coming to power in the USSR, amid heightened Cold War tensions owing to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, across the ocean US President Jimmy Carter signed the notorious Directive 59 (pD-59), 'Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy', which was aimed at giving US leaders more flexibility in planning for and executing a nuclear war. However, leaks of its 'top secret' contents gave rise to front-page stories in the New York Times and Washington Post that stoked widespread fears about its implications for unchecked nuclear conflict.

The document presupposed the use of advanced technology to detect Soviet nuclear facilities, including in Eastern Europe and North Korea. The Americans planned to carry out precision strikes on these sites and, having received data on the damage done as quickly as possible, to strike again if necessary. The authors of Directive 59, among whom was the presidential military adviser William Odom, believed that the use of nuclear weapons against regular units of the Soviet army would not lead to a nuclear apocalypse. Yet, Odom and his colleagues warned that the war would be prolonged – in their estimation, it could take “days and weeks” to find all the targets worthy of a precision nuclear strike.

In 1983 – a year before Chernenko ascended to Kremlin leadership – the US delivered its new Pershing II nuclear missiles to West Germany. This significantly increased the possibility of such weapons reaching the USSR in a matter of minutes.

So, what if Chernenko – “a bent figure, trembling hands, a breaking voice calling for discipline and selfless work, sheets of paper falling from his hands,” as described by Gorbachev – had to make a decision on a nuclear counter-attack? What if the whole leadership was dead before they had the chance to order a retaliatory strike? Who would contact remote command posts and submarines?

That exact fear, of a country beheaded, a country denied a chance to respond, a vulnerability leaving no space for reacting, had made the Soviets start considering their options. The ‘if I'm going down, I'm taking everybody with me’ approach was a way of proving that there could not and should not be winners in future world wars. This argument was supposed to make war so meaningless that it would become impossible.

The Doomsday system

In 1984, right after Chernenko became the new Soviet leader, Valery Yarynich, a colonel in the Elite Strategic Missile Forces, acquired a new position, that of deputy head of the Main Directorate of Missile Weapons. It was this colonel who was entrusted with perfecting a flawed system, partially automated, that would launch intercontinental ballistic missiles in a retaliatory strike if the Soviet leadership had been decapitated in a nuclear bombing.

The system – probably the deadliest project of the Cold War – was called Perimeter, or ‘the Dead Hand’, informally. It was put on combat duty in 1983.

The Soviet Union could not have been the one to launch a nuclear ICBM at the Americans first. In this scenario, the US would have had enough forces left to inflict significant damage in a retaliatory strike with the remaining means at its disposal. It was also dangerous to launch missiles after detecting American warheads heading toward the USSR, since by that time there had already been several cases of false alarms from the warning systems. The only way left was to strike back only after confirming an attack by the enemy. But this was overly dependent on the state of mind of the general secretary. He could be frightened, confused, or too slow to act, or could believe it to be another false alarm.

The developers of Perimeter tried to minimize human interference. All that the general secretary had to do after receiving any information about an enemy strike was to place Perimeter on alert. After that, the fate of humankind passed into the hands of officers, who would have to make a decision. They were isolated in special spherical bunkers so deep underground that even a nuclear strike could not destroy them. These officers had a list of three criteria for launching an attack:

– Status of the Perimeter system. If it was activated, it meant that either the general staff or the Kremlin had put it on alert.

– Communication with commanders and party leaders. If this was lost, it was to be assumed that the leadership had been killed.

– The fact of a nuclear strike. At the same time, a network of special sensors was used to measure the level of radiation and illumination, seismic shocks, and an increase in atmospheric pressure.

If the system was activated, the leadership was dead, and a nuclear strike had indeed taken place, the officers had to authorize the launch of the command missiles. In 30 minutes, they would have given the order to launch all nuclear missiles that were still intact. The target was the US, along with other major NATO capitals.

According to Yarynich, the system also served as insurance against hasty decisions by the country's top leadership based on unverified information. Having received a signal from the missile attack warning system, the top officials could activate the Perimeter system and wait for events to evolve, being fully confident that even the destruction of everyone who had the authority to issue a command to retaliate would not be able to prevent a retaliatory strike.

One of Perimeter's developers, Alexander Zheleznyakov, described a possible scenario for using the system as follows:

“Two hours after the start of hostilities, when it seemed that there was nothing and, most importantly, no one to fight, in the remote Siberian taiga, in the Kazakh steppes, in the swamps of central Russia, the hatches of mine launchers almost simultaneously opened, and dozens of silver giants rushed into the sky. Thirty minutes later, the fate of Moscow and Leningrad, Kiev and Minsk, Berlin and Prague, Beijing and Havana was shared by Washington and New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, Bonn and London, Paris and Rome, Sydney and Tokyo.

Having suddenly started, the nuclear war ended just as suddenly, destroying everyone. There were no winners or losers. Only small groups of people who did not understand anything somewhere on the islands of the Pacific Ocean, in remote areas of Africa and Latin America, feverishly turning the knobs of silent radios at once, watching with fear the lightning flashes blazing over the horizon.”

However, it was still the officers who had to make the last call on the strike that would destroy most of humankind. The question remains whether Perimeter's developers went further and made the system completely autonomous, turning it into a true Doomsday Machine. Yarynich claims that the generals did not agree to this, although the opinions of his colleagues differ. He also told journalist David Hoffman he believed that it was utter stupidity to keep the Dead Hand secret, since such a system was useful as a deterrent only if your adversary knew about it.

Is the Dead Hand dead?

Yarynich was the one to blow the whistle on Perimeter after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In the early 1990s, he spoke cautiously about the key details of the Dead Hand system with American nuclear security expert Bruce Blair, who revealed the existence of the system in a New York Times op-ed, not mentioning the Russian colonel, though his colleagues were well aware who had leaked the information. In 2003, Yarynich himself wrote a book, ‘C3: Nuclear Command, Control, Cooperation,’ providing even more details. He had spent the rest of his life fighting for transparency within the nuclear command and control mechanisms of Russia and the US. “Nuclear weapons should not be viewed as a political instrument,” he believed.

“Today, we are facing an obvious absurdity,” Yarynich wrote in the introduction to his book. “On the one hand … the United States and Russia have become unprecedentedly open with each other, exchanging information that used to be completely secret during the Cold War.”

“Now publicly accessible computer databases include information about the various types of American and Russian ballistic missiles and nuclear warheads, their numbers, characteristics, location, design bureaus and production facilities … The results of such decisive steps is evident: the process of nuclear arms reduction has started and is successfully continuing.”

However, Yarynich argued, this isn’t enough: absolute secrecy still reigns when it comes to command and control of nuclear weapons.

“Two issues are of greatest importance here,” he explained.

“First, what measures have been taken by the nuclear powers against accidental or unauthorized use of nuclear weapons, and how reliable are those measures? Second, what is the ideology for hypothetical authorized deployment of nuclear weapons?”

In 2007, Yarynich gave a detailed interview to Wired magazine. In it, he repeated his story about the technical features of the Perimeter, and most importantly, confirmed that the system is constantly being updated, and that he's proud to have been involved in its development: it successfully managed its task in the Cold War and can continue to serve. All he wanted was for the system to be talked about. Yarynich believed that publicity around the system would be useful to Russia: no one wants to die in vain.

According to Pyotr Kazulsky, a former researcher at the Research Center for Applied Informatics, today the Perimeter system has been updated and the new control center is equipped with a neural network. There is no confirmation of this. There are no other sources who would talk about it, so the 'singularity' upgrade remains a rumor – and will probably stay this way, since all information about the system (and its analogue) is classified. Bruce Blair has also repeatedly claimed that the system is constantly being updated.

In December 2011, the commander of the Strategic Missile Forces, Lieutenant General Sergei Karakaev, stated that the Perimeter system exists to this day and is on alert.