First man in space: How a Russian pilot fulfilled mankind’s dream to leave the planet

Wednesday marks the International Day of Human Space Flight — known in Russia as 'Cosmonautics Day — dedicated to the first manned mission. Exactly 62 years ago, on April 12, 1961, a citizen of the Soviet Union, Senior Lieutenant Yuri Gagarin, made his orbital journey around the Earth. His voyage on the Vostok spacecraft inspired the world and wrote his hame into the history books.

This feature was first published on March 27, the 55th anniversary of his tragically early death.

On the chilly morning of March 27, 1968, the low gray sky of the Kirzhach area of Russia's Vladimir Region was pierced by the roar of an engine. A two-seat jet fighter plummeted through the rainy clouds, cutting off the tops of trees and disintegrating in flight before hitting the ground at great speed. An explosion followed. A piece of a flight jacket was left hanging on a birch tree. In the pocket was an unused breakfast ticket: With the name "Gagarin Yu. A."

Arguably, the most famous person on the planet had died – an internationally recognized hero, the idol of Soviet youth, the first person in space. The results of an interdepartmental investigation of the crash were collected in 29 volumes, and its final verdict was classified by the authorities. How did Yuri Gagarin die?

Maiden flight

In his biography, the legendary cosmonaut has been portrayed as the boy next door – the third child of a carpenter and a dairymaid from a small central Russian town. During the Second World War, he and his family lived under Nazi occupation. His parents did not collaborate with Adolf Hitler's men, nor did they engage in partisan activities – they merely survived.

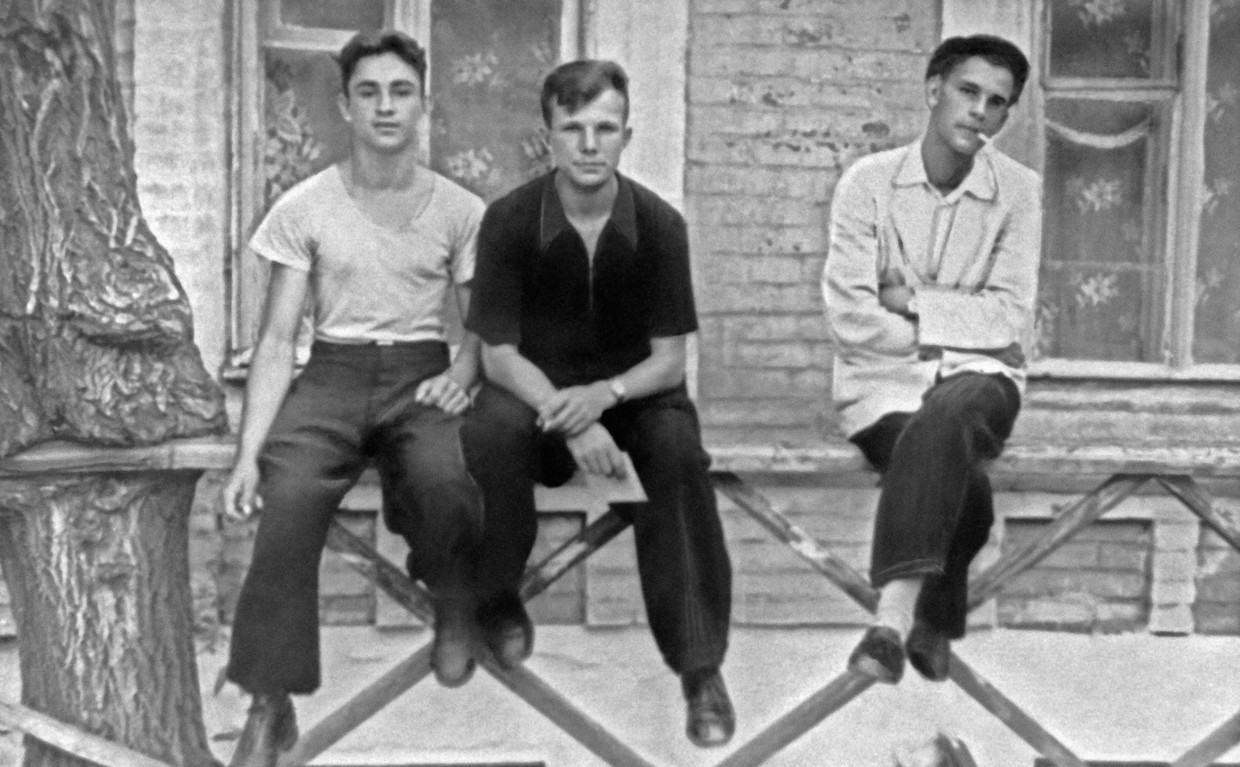

After the war, Yuri moved to Moscow – after finishing sixth grade – and entered a vocational school. He began learning the mold maker’s trade and joined the Komsomol youth organization. Having mastered a basic profession, Gagarin entered the industrial college of Saratov, where he became known for his athletic abilities and character.

Soon, the future pilot took an interest in aviation, an area which enjoyed great popularity in the USSR, as the Kremlin leader Joseph Stalin placed great emphasis on its development. Gagarin joined the aeroclub of the DOSAAF Soviet defense and sports organization. This undertaking presented no problem for the excellent student and Komsomol member, who made his first independent flight at the age of 21 on a Yak-18 training aircraft. In total, Yuri completed 196 flights in the aero club and flew 42 hours and 23 minutes.

That same year, Gagarin was drafted into the army, where he was assigned to an aviation school and even appointed assistant platoon commander. He was an excellent student in almost all piloting disciplines – only landing was a problem. This was typical for short pilots – due to his stature, the viewing angle was impaired. As a result, Gagarin tended to slam the plane on the runway. To solve this issue, he put a thick cushion on his seat so he could see the front of the aircraft better. He graduated with an ‘excellent’ mark in the fall of 1957 and was sent to serve in the Northern Fleet, where he flew a MiG-15 fighter.

As an excellent student of combat with sound physical and political training, he was soon chosen for the first cosmonaut squad of 20 people, created in April 1960.

Psychologists noted his lively, proactive character:

“He loves events with lots of action, where heroism, the will to win, and the spirit of competition prevails. In sports, he takes the role of initiator – the leader and captain of the team. As a rule, his will to win, endurance, determination, and understanding of his team play a role here. His favorite word is ‘work’. He makes sensible suggestions at meetings. He is always self-assured and confident in his abilities.”

But this didn't matter much to the Soviet space program, which was in a race with the US, and needed to speed up its development. The R-7 launch vehicle created by designer Sergey Korolev had some well-known flaws.

From the point of view of the designers, the main requirements were that they were fighter aviators accustomed to high G-forces who were no more than 170cm tall, weighed no more than 70 kilograms (to fit into the Vostok capsule), were aged 25-30, physically fit, disciplined, and psychologically stable. There was not much confidence in the last point, so the designers came up with a kind of ‘fuse’. It was thought that the first person in space might panic and try to manually take control of the spacecraft. In anticipation of this, he was given an envelope with a complex mathematical problem – only by coming to his senses and solving it could the cosmonaut take the reins.

In general, the design specialists took a utilitarian approach to selecting cosmonauts. The final decision on would fly to space was made by the head of the Soviet state, Nikita Khrushchev, who had succeeded Stalin. Perhaps it was Gagarin’s ordinariness, his lack of awards and serious track record, that played a decisive role. If Lenin posited that “any cook can run the country,” then Khrushchev held that ‘any mold caster can fly into space.’

Golden boy

It was Khrushchev who made Gagarin a superstar. However, before becoming the most famous person in the world, Yuri had to practically disappear. In the atmosphere of the Cold War, the USSR could not afford even a chance of public failure, so the launch of the rocket on April 12, 1961 was carried out in the strictest secrecy. Yuri’s wife and daughters did not even know about the flight. The farewell letter written to them before the launch would be published many years later, after Gagarin’s actual death.

However, as soon as it became clear that the flight was successful and the cosmonaut had returned alive and well, an almost endless series of celebrations and receptions began. At the landing site, Gagarin was awarded the somewhat ironic ‘For the Development of Virgin Lands’ medal. At the airfield in the city of Engels, he was handed a congratulatory telegram from the Soviet government, and the Air Force command and journalists arrived there a couple of days later.

The voice of TASS, Yuri Levitan, announced to the whole world that the first manned space flight had been piloted by Soviet citizen Gagarin. The cosmonaut personally reported on the successful flight to the highest government officials via a secure line. After that, the he was transported to a government dacha in Kuibyshev on the Volga, and a couple of hours later, designers and program managers headed by Korolev arrived and sat down to celebrate at nine in the evening. This was only the first party for the Soviet officer, who had been a complete unknown in the morning, writing a farewell letter to his wife. It was far from the last.

A day later, the cosmonaut was met in Moscow. Khrushchev personally secured Gagarin’s promotion from senior lieutenant to major from the reluctant defense minister, Rodion Malinovsky. On approach to Moscow, his plane was met by a solemn escort of seven MiG-17 fighters. The flying motorcade passed over the center of the capital and Red Square, and landed at Vnukovo. A red carpet was stretched from the ramp to the podium, along which cheering people, journalists, and cameramen stood. Gagarin walked down the path to Khrushchev with his shoelace untied.

To the cheers of the welcoming crowds, Khrushchev and Gagarin rode in an open limousine to Red Square, where Gagarin was awarded the titles ‘Hero of the USSR’ and ‘Cosmonaut of the USSR’ at a solemn ceremony in the presence of the country’s highest officials. The rally lasted three hours, and another private gathering in the inner halls of the Kremlin went on for another three. A press conference for the foreign press was scheduled for the next day.

Gagarin was given practically no time to recover. He became Khrushchev’s main PR tool in the international arena. Even during the five-day post-flight medical examination, two Pravda newspaper correspondents were assigned to the cosmonaut to write an autobiography, ‘The Road to Space’. On April 28, just two weeks after his legendary flight, he went to Czechoslovakia, from which his world tour began. In May, he was in Bulgaria; in June, Finland; and in July, the UK.

It is noteworthy that Gagarin, a foundry worker by profession, was invited to Britain by the general secretary of the foundry workers’ union. There, he had lunch with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, laid a wreath at Karl Marx’s grave, and had breakfast with the Queen. She even agreed to a joint photo in violation of protocol. Gagarin was no longer an earthly man – he was capable of anything.

He returned to Moscow on July 15, but was already off to Poland on the 20th. After celebrating the 17th anniversary of the liberation of the country from the Nazi invaders and participating in an all-Polish youth rally in Zielona Gora, he returned to Moscow on the evening of the 22nd. At midnight the next day, he was already on his way across the Atlantic, visiting Iceland, Canada, and of course, Cuba, where there was a big celebration and a reception with Fidel Castro. Then, he went on to Curacao, Brazil, and returned by the same route. In August, he was feted in Hungary; in November, in India and Sri Lanka; and in December, in Afghanistan.

This went on for quite a long time: Egypt, Libya, Ghana, Liberia, Greece, Cyprus, Austria, Japan; again Finland, Denmark, and France; again Cuba, Mexico, and East Germany; and in October 1963, he visited the US at the invitation of the UN secretary general. Then Sweden, Norway, and again, France.

Obviously, there were solemn meetings, receptions, rallies, speeches, and breakfasts with monarchs everywhere. In Norway, the cosmonaut went to the sea to fish and visited the Grieg Museum at the request of Norwegian sailors. Gagarin lived according to this crazy regime for almost three years. It was said that he began to drink a bit, his former work routine completely forgotten.

Too Fast, Too Reckless

Finally, Gagarin’s name gradually began to disappear from the front pages of the world media. And for Khrushchev, Gagarin’s biggest international promoter, an uneasy situation began, which ended with his resignation.

The 30-year-old colonel, who was at the peak of his fame, had to integrate back into normal life. In between trips, he attended classes at the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy. But his main task was to prepare for the next space flight and return to permanent service in fighter aviation.

It was determined that, over the years of his tours, he had lost the qualifications to be a fighter pilot and needed to be retrained. As part of this process, a routine flight took place on March 27, 1968. Yuri was familiar with the plane – a training modification of a MiG-15 with a paired cockpit for an instructor and additional fuel tanks. The instructor was Vladimir Seregin, an experienced test pilot of the 1st class who had received the Hero’s Star for assault sorties during the Great Patriotic War. It was assumed that, in the event of an emergency, control of the aircraft would pass to him. One peculiarity about the training MiG-15 was that the instructor himself had to eject before the pilot could.

The weather was unpleasant, but it was acceptable for a simple flight task – low clouds with a couple of kilometers of clearance above, and then thick clouds again. Gagarin and Seregin’s plane took off at the Chkalovsky airfield at 10:18 in the morning. The task should have taken about 20 minutes, but at 10:30, Gagarin reported its successful completion and requested permission to turn around and return to base. The plane was not heard from again.

The search for the wreckage took quite a long time. The crash site was finally found at 2:50pm about 65 kilometers from the airfield, 18 kilometers from the city of Kirzhach in Vladimir Region. The State Commission started working the next day.

The shocking death of the first man in space, the large-scale investigation, and the secrecy of its results sparked numerous rumors about the causes of the disaster. Some believed that the all-powerful KGB had decided to remove the popular figure. Others speculated about a UFO encounter. Another story was that Gagarin and Seregin had died a few days earlier during the completion of the L-1 lunar flyby program. And, of course, there was the inevitable conjecture that the pilot and the instructor had taken a glass of vodka before departure.

More reasonable theories envision the dangerous approach of another aircraft performing training tasks in the same area, which caused the plane to fall into a tailspin in its wake. The idea that the cabin had depressurized due to a collision with a weather balloon was also put forth.

The most logical theory still seems to be that the crash was due to a piloting error and bad weather data. Having had many calm, routine flights, Gagarin completed the task in a band of acceptable cloud cover twice as fast as he should have, reported to the ground that he was returning, and dove down through a solid cloud bank. According to his and Seregin’s calculations, they should have emerged from the clouds and seen the horizon at an altitude of about 900 meters, but the clouds had fallen lower. When the pilots finally saw the ground, there was no time to pull out of the dive at such speed with so much momentum, although both officers fought until the last moment to level the plane.

The self-confidence of an impatient ace, who had grown accustomed to celebrations, balls, and his own exceptionalness, compounded by rapidly changing weather conditions, most likely caused the tragic accident. The banality of this version also explains its secrecy. The Soviets could not put the first man in space and then have been seen to so stupidly fail to protect him. It was better to let rumors circulate among the people than allow the whole world to find out about the simple mistakes made in the preparation and execution of routine training flights. Gagarin and Seregin were cremated the day after their deaths. Their ashes were placed in the necropolis of the Kremlin Wall.