Inside Europe's largest salt mine: Wagner Group fighters offer a tour of the huge Donbass facility captured from Ukrainian forces

In mid-January, Russian troops entered Soledar, where Artemsol – the largest salt-mining enterprise in Europe – is located. An RT correspondent visited the Donbass city this spring and explored one of the mines with the aid of PMC Wagner fighters.

Learn more about their descent 300 meters underground, see bas-reliefs made of the substance, and delve into the history of one of the oldest such deposits in the world in RT’s photo report.

Salt has been an indispensable part of human life since time immemorial. An important item of trade, it has at times been a decisive factor in economic stability, while wars have even been waged over possession of this mineral. Unsurprisingly, salt mining was among the first industries in Ancient Rus.

Soledar, though itself not dating back to the Middle Ages, is inextricably linked to the extraction of salt. The first mention of settlements in the area dates back to the end of the 17th century, when the village of Bryantsevka appeared in the vicinity of the deposits. By the end of the 19th century, deep salt beds had been discovered here, and construction of the first mine began.

Production peaked in Soviet times, when the Artemsol enterprise accounted for about 40% of the rock salt production in the entire USSR. In its most successful years, the enterprise could produce over 7 million tons annually, which is comparable to the modern production of Brazil (6.3 million tons per year) and Canada (10 million tons per year). Today, only about 2 million tons of salt are mined per year in Russia.

Despite the large production volume, only 218 million tons have been extracted over the past 140 years – about 3% of the total deposit. This means that there is enough remaining to last for over 1,000 years. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s only remaining salt mines are located in the western part of the country.

In recent times, one of the mines at Artemsol was turned into a speleotherapy sanatorium, where respiratory illnesses were treated. Tourists could also visit some mines on guided tours, and there is a salt industry museum and a church – both located underground.

Other drifts were used as warehouses for storing weapons and explosives, although at the time of my visit they were empty. (According to recent information, the largest warehouses for storing weapons and ammunition came under Russian control in the village of Paraskovevka, south of Soledar.) In one of the mines we found a neutrino detector, one of two such apparatuses created in the Soviet Union.

This salt deposit began forming from an ancient sea around 250 million years ago, during the Permian period. Present-day Donbass is located at the site of a shallow lagoon of the ancient Perm Sea. As the water evaporated, the mineral gradually settled at the bottom of the lagoon.

The vertical mineshaft is similar to those used for the construction of subways and bomb shelters. Only this one is much deeper, reaching 290 meters beneath ground. The walls are lined with cast-iron tubing, as in metro tunnels. Since the elevators are currently damaged and cut off from power, the only way down is via an endless staircase, which took us about an hour to descend. A flashlight doesn’t illuminate the bottom of the mineshaft, and it’s impossible to estimate its depth with the naked eye.

Our journey began at the concrete ventilation shaft. When the mine was in operation, stable levels of pressure, temperature, humidity, and oxygen were maintained here. Presently, however, all ground systems have been damaged or cut off from power, and the temperature below ground is noticeably warmer than on the surface.

The salt produced at Artemsol was exported to 22 countries. The main consumers were Poland, Austria, Hungary, Finland, Germany, and Denmark. Russia was also among the top importers of salt (mainly the technical variety) – in fact, the Russian market accounted for more than half of the enterprise’s output.

The wall on the left bears the characteristic imprint of the combine’s incisors. These tunnels were dug with a special machine that cut through the rock from top to bottom. By counting the number of round recesses at the end of the tunnel (in the photo above, there are only two), it is easy to guess the number of times the combine passed through here.

In over a hundred years of mining, the underground system of tunnels has greatly expanded and now reaches about 300 kilometers in length.

The walls are made of pure salt – the sodium chloride content here exceeds 98%. Most of the salt cut by the combine can be immediately packaged and sold.

We approach mine No. 3. This is one of the oldest chambers and among the main tourist attractions in Soledar. Before the war, thousands of tourists visited it annually.

The museum, speleotherapy sanatorium, and currently empty weapons warehouses were all located here. Above ground, the war continues, and despite the depth of the mine, we can still hear distant volleys of artillery fire.

At this depth, the tunnels stretch for hundreds of kilometers, connecting the mines that were in operation until last year.

One of the Wagner fighters who accompanied me tried to start a diesel transport vehicle. However, all attempts were unsuccessful since the battery had died.

Since the 1960s, these warehouses were used for storing old weapons, such as Mosin rifles (from the times of the Russian Empire), Shpagin submachine guns (Second World War era), and seized German weapons. But the warehouses that we visited turned out to be completely empty.

In another drift we found a recreation zone with a bar. The huge empty chamber is furnished with cheap plastic figures and seats from IKEA.

Salt was once extracted here as well, but later these mines were used for medical purposes and shown to tourists.

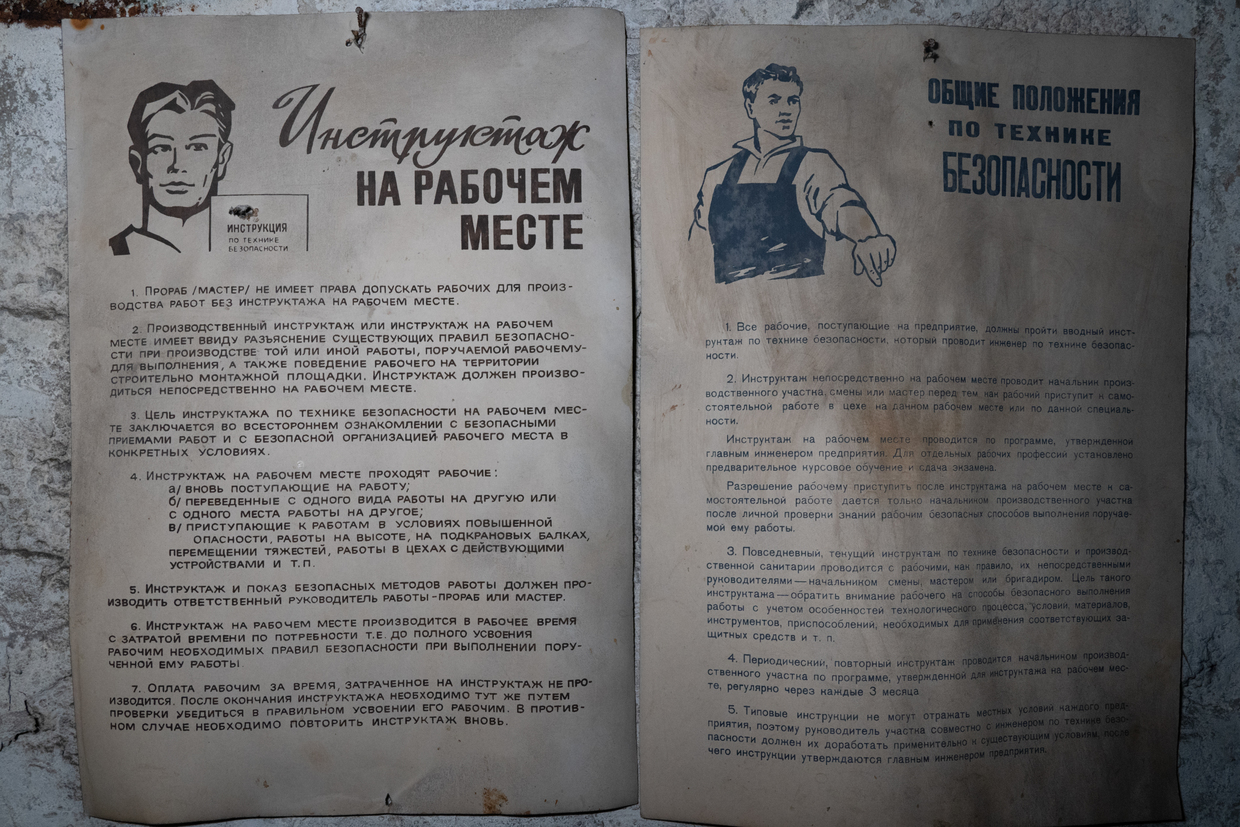

The Soledar salt deposit recently celebrated its 140th anniversary, as is evident from a Ukrainian poster.

The walls of the mine are decorated with various bas-reliefs made by several generations of miners and later, when salt was no longer extracted in these drifts, by professional sculptors.

When the city was stormed, Russian troops assumed that the enemy would use the mines for defense purposes. However, no underground battles took place here.

Ukrainian forces were positioned only at the entrance to the shafts, because they realized that going down would mean condemning themselves to a certain death – the only way up was through a limited number of exits, all of which were soon blocked by Russian fighters.