Less media, more sedatives: Oklahoma reviews capital punishment protocols after botched execution

Oklahoma announced that more sedatives and less media, among other measures, are part of the state’s new protocol for capital punishment after a botched execution in April left an inmate writhing in pain before dying 43 minutes after a lethal injection.

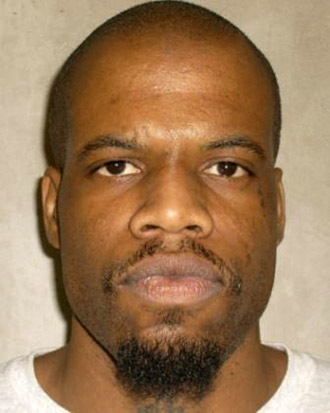

The state revealed Tuesday that it will increase the amount of midazolam it employs during executions. Prison officials said the use of the controversial sedative can be as much as five times the amount used to kill Clayton Lockett in April.

Oklahoma will also demand more training of prison staff and members of execution squads while outlining contingency plans in case of equipment malfunction or a problem with an inmate’s medical condition.

The state will also reduce the number of media witnesses allowed at executions from 12 to five.

Robert Patton, the director of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections, would not comment to AP on the new guidelines based on litigation over Lockett’s death.

Twenty-one death row inmates sued the Department after Lockett’s bungled execution. Lockett died after doctors burst a vein in his body administering a controversial cocktail of drugs. As RT reported in April, the drugs leaked out of his vein as a result, and an unknown amount was absorbed into his body. Although lethal injections typically take about 10 minutes or so to kill an individual, Lockett’s procedure lasted for 43 minutes, during which he reportedly writhed, groaned, and clenched his teeth before officials closed the blinds from witnesses’ view.

The incident triggered an investigation, ordered by Gov. Mary Fallin. The new protocols are the result of that probe, which ultimately blamed the excruciating manner in which Lockett died on a misplaced intravenous line in his groin, and on a decision by the warden to obscure view of the IV site with a sheet.

Yet the supposed solutions that have come from the investigation are not enough, according Dale Baich, assistant federal public defender who is representing the inmates that sued the Department of Corrections.

“We still do not know what went wrong with Mr Lockett’s execution,” Baich said.

“Discovery and fact-finding by the federal courts will address those issues,” he added.

Baich also said the new media provision “reduces public accountability and makes the process less transparent.”

Oklahoma is one of many states - including Florida, Missouri, Arizona, Ohio, and Texas - that have turned to secretive sources, often compounding pharmacies, to supply execution‘cocktails’ using unproven drugs to carry out capital punishments. These actions were the result of the European Union’s ban - in place over moral objections to capital punishment - against its pharmaceutical companies selling to US state correctional departments drugs that could be used in lethal injections.

Yet, compounding pharmacies do not produce their drugs under regulations enforced by the Food and Drug Administration, causing many to question just how safe they are and further calling into question how humane or ethical the death penalty can be considered.

Outside of Oklahoma, many inmates and media outlets have sued to force states to disclose exactly what drugs will be used for lethal injections, as well as their source, but these efforts have generally failed in court.

Midazolam is a sedative often given to patients before surgery, and is used in executions as a piece of a three- or two-drug cocktail. While a normal medical dose is 5 milligrams, Oklahoma was administering 100 milligrams for lethal injections. The new protocol will use a recommended 500 milligrams for executions, the same amount used in Florida.

“The prisoners still do not have access to information about the source of the drugs, the qualifications of the executioners, or how the state came up with the different drug combinations,” Baich said of Oklahoma’s revised procedures.

Three Oklahoma inmates are set to be executed this fall. Charles Warner, who was supposed to die the same night as Lockett, is scheduled for Nov. 13. Richard Glossip and John Marion Grant are due for execution on Nov. 20 and Dec. 4, respectively.

In early September, a federal judge urged the state to come to a conclusion regarding its investigation of lethal injection procedures prior to the trio of executions this fall.

In multiple cases this year, executions using the secretive drug cocktails have gone wrong, with inmates subjected to long, painful procedures that critics say violated their right to be protected from cruel and unusual punishment. In Ohio, death row inmate Dennis McGuire took more than 20 minutesto die after drugs were administered, during which he reportedly made choking sounds and gasped for air.

US President Barack Obama called Lockett’s botched execution “deeply disturbing” and called for a review of death penalty procedures in the United States.