Think pink: Number of women with breast cancer may double in next 15 years, study finds

By 2030, the number of women expected to develop breast cancer will increase by about 50 percent, according to a new study. Currently, one in eight women will develop the disease at some point in her lifetime.

The study combined two types of breast cancers ‒ invasive and in-situ ‒ to make its projections, according to study author Philip S. Rosenberg, PhD, a senior investigator in cancer epidemiology and genetics at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Breast cancers are the most common type of malignant tumors in the US, with 283,000 diagnosed cases in 2011. That number is expected to rise to about 441,000 in 2030, researchers found.

The numbers the team put forward in its study aren’t as scary as they seem, though, because the increase is driven by three factors, Rosenberg said.

Firstly, people are living longer, so women who don’t die of other causes are more likely to develop breast cancer. Secondly, there are more female Baby Boomers than there were women of the Greatest Generation, and those Boomers will reach an age where they are more likely to get breast cancer over the next 15 years. Finally there is a rising rate of estrogen receptor (ER) positive cancer, which the study projects forward.

Wow. Breast #cancer rates will increase by 50% by 2030,” according to new research http://t.co/Ge2jdwcQAp

— Mid Life High Life (@MidLifeHighLife) April 20, 2015

Rosenberg and his colleagues sought to estimate the future incidence of new cases of breast cancer, as well as the burden those cases will put on the health care system. They believe their estimates will help the oncology community to “develop a proactive roadmap to optimize prevention and treatment strategies,” they said in a statement.

"Although breast cancer overall is going to increase, different subtypes of breast cancer are moving in different directions and on different trajectories," Rosenberg said in the statement, referring to whether tumors are invasive, in-situ or ER-positive or ER-negative.

“These distinct patterns within the overall breast cancer picture highlight key research opportunities that could inform smarter screening and kinder, gentler, and more effective treatment,” he continued.

The NCI group found that the number of ER-negative breast cancers is expected to drop in coming years, and those tumors can be among the most difficult to treat, Rosenberg told HealthDay.

"There could be a breast cancer-prevention clue in that decline," Rosenberg said. "Understanding the 'why' behind the trend will be very important."

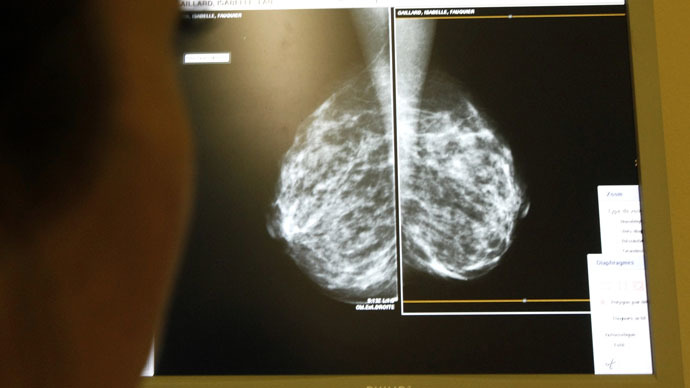

Another factor that increased the projected breast cancer rate is the NCI study’s inclusion of carcinomas in-situ (CIS) ‒ or smaller tumors that have not spread to neighboring tissues. There is a debate as to whether CIS should be considered a cancer at all, and whether early screening through mammograms and monthly breast self-exams leads to over treating tumors that may not have grown or become malignant.

“There’s certainly concern, especially in the older patients, about over-diagnosis of breast cancer, and that’s one of the reasons that screening mammography can become very controversial in older patients,” Dr. Sharon Giordano, MPH, department chair of health services research at MD Anderson Cancer Center, told Time. “We don’t want to end up diagnosing and treating a disease that would never cause a problem during the person’s natural lifetime.”

Not all in-situ breast cancer progresses into a dangerous condition, said Giordano, who was not involved in the research.

READ MORE: FDA approves Google-backed home genetic test

“One of the unanswered questions is, how do we identify the in-situ cancers that are the ones that go on and progress to a life-threatening illness, and which are the ones that we should be leaving alone and not subjecting people to invasive surgery and radiation for treatment?” she asked.

Last July, a panel from the National Cancer Institute concluded that improved screening has resulted in the over-diagnosis and over-treatment of cancers that are not life-threatening, without significantly reducing the death rate from the disease, the Washington Post reported.

Rosenberg will present the study’s finding at the American Association for Cancer Research’s annual meeting this week. His team used cancer surveillance data, census data and mathematical models to arrive at their projections.