2017 could have been year Russia and US made up. Now they stand on brink of new Cold War

On this day 12 months ago, Moscow held off from retaliating to Barack Obama's diplomatic parting shot, in hope of a new start. Instead, 2017 has been the worst year of US-Russia relations since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Three weeks before leaving the Oval Office, Obama expelled 35 Russian diplomats and closed two Moscow-owned properties in the US over claims of election meddling. Counter-measures were expected.

“I invite all children of US diplomats accredited in Russia to the New Year and Christmas children’s parties in the Kremlin,” Russian President Vladimir Putin announced instead, capitalizing on the moment to show unexpected festive magnanimity.

Yet by that point Russia’s bogeyman role as the explanation of the Democrats’ loss in the 2016 election, and the weapon with which to delegitimize the incoming President Donald Trump, was set. ‘Shattered’, the sympathetic chronicle of Hillary Clinton’s doomed presidential run, details how “less than 24 hours after the concession speech” her campaign manager John Podesta and his team gathered at their emptying headquarters to forge the narrative for the coming months in which “Russian hacking was the centerpiece.”

On January 10, 2017 BuzzFeed published the DNC-funded Christopher Steele dossier – a historic document not for the revelations contained therein, but as a marker for the strength of sentiments against Donald Trump, and a watershed for the deliberate dropping of US journalistic standards for a political cause.

Tit-for-tat

An alliance between the bitter Republican establishment and vengeful Democrats has since formed in Congress, driving the anti-Russian agenda throughout the year. The sanctions bill overwhelmingly passed in July designated Russia alongside Iran and North Korea as America’s official “adversaries.” It also charged Moscow with such a wide-ranging list offenses – encompassing Ukraine, Syria, hacking, energy security threats – and a similarly lengthy list of targets – from politicians, to oligarchs, to companies, to banks – that even with the best will in the world, it is not clear that the Kremlin could fulfil any specific criteria to have them removed.

Congress also did not pass up the opportunity to humiliate its president like an untrustworthy child, by placing severe restrictions on Trump’s ability to loosen any of the measures regardless of international dynamics, thus rendering all future diplomatic efforts likely futile. Hence the pitiful sight of Trump signing the bill into action even as he denigrated it as “deeply flawed.”

Unsurprisingly, Moscow said that the measures would result in an “out-and-out trade war” while Putin called them “illegal” and bemoaned that “US-Russian relations are being sacrificed to resolve internal policy issues.”

The act gave the start to the most unedifying tit-for-tat saga of the year, in which both sides tasked themselves with calculating exactly how many consular staff they needed to expel to reach “parity”in the stand-off, and arguing over whether each step was an escalation or merely the just response in the dispute.

In response to Congress and those initially unanswered expulsions, Putin ordered US missions to reduce their payroll by 755 employees. One month later, in late August, the White House gave Moscow 72 hours to shutter three of its diplomatic buildings, including its oldest consulate in San Francisco, which in turn led to threats of lawsuits from the Russian side, unhappy about being forced out of properties it owns.

The drip-drip of hostilities has carried on through the past three months, with many of the announcements centered on international media. Following the US order to single out RT America as a “foreign agent” – a designation originally created to root out Nazi propagandists before World War II – Washington and Moscow have engaged in one-upmanship, with the Russian Duma passing a mirror bill, which reduced what was already a nebulous term into a playground insult. In an example of the pettiness and the low stakes, RT has been stripped of its congressional credentials and US reporters can no longer visit the Duma.

Containing Russia?

None of the above measures will pave the way for a détente, but what if this is not the American aim? After all, the White House’ national security strategy published earlier this month talks of “preserving peace through strength, and advancing American influence in the world” all while promoting “our way of life.” In turn, Russia is described as “challenging American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity.”

If the US yardstick of success is not peace but domination, then punishing the Kremlin is a success, and the question becomes, “is the US treatment of Russia effective in asserting its superiority and changing Moscow’s behavior?”

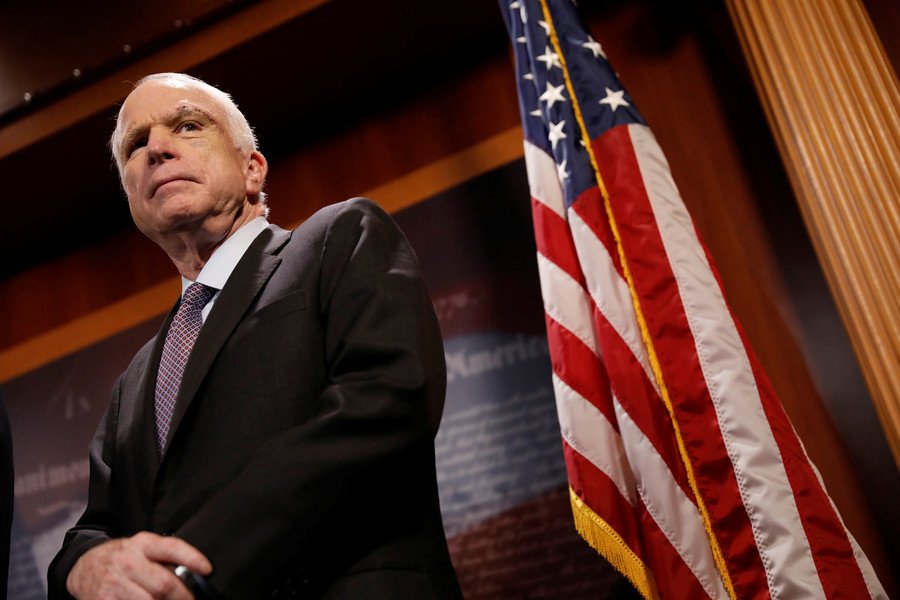

But on this score 2017 has also been a failure for the US, due to a lack of a coherent approach, as even John McCain would admit. Trump has spoken of “healing” relations with Moscow – that talk has been echoed by his lieutenants – and does not come across as an obvious figurehead in a new Cold War. However, he hasn’t been so much as able to exchange several words with Putin at an official dinner without being branded a traitor by large swathes of the establishment. On the other hand, no one appears to have been pushing Trump to order the consulate closures, which aggravated the Kremlin more than the more substantial but less arbitrary moves. And yet when Trump made the decision, was he really motivated by a desire to achieve geopolitical results, or as a means of deflecting accusations about being friendly to Russia? Or did he do it at the behest of security and military officials – the same ones whose hand can be seen in the latest doctrine?

This is chaos.

From the angle of effectiveness, if anyone has gained from the erratic US policy-making it is Putin, who looks measured, consistent and statesmanlike in his pronouncements, while his officials speak with one voice, as Russia has clearly pursued a number of international policies over a period of several years.

Lose-lose

While Putin can take solace from his increasingly prominent portrait as an international diplomatic mastermind outwitting the hapless Trump, it is obvious that the last 12 months have been a lose-lose proposition for both Washington and Moscow. The simmering morass leaves Russia cut off from the West, in a situation where international sanctions become the 'new normal.' Meanwhile, the White House misses out on a potential economic and diplomatic partner on issues from the Middle East to North Korea to the Arctic, and retains a regional rival forever capable of throwing around its international weight or scuttling a UN Security Council resolution.

Ironically, 2017 was geopolitically an opportune year for the two countries to mend relations. Both countries can take credit for defeating ISIS – and not catching each other in the crossfire. The Syrian conflict has swung decisively to President Bashar Assad’s government, with the White House fully aware that from now on deal-making could bring greater dividends than pouring more money and goodwill in the black hole of supporting the opposition. The Ukrainian conflict remains intractable, but has receded in diplomatic importance, while accepting Crimean secession as a fait accompli has become plausible enough if the issue is not to poison Moscow-Washington relations for decades to come.

Even if circumstances continue to be favorable in 2018, prospects for a thaw remain thin. The Democrats will not let go of the Russia-Trump story even if the investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller yields no smoking gun, while specific sanctions against Russia as a result of July’s law will likely power a new spiral of strife. Putin is the overwhelming favorite for re-election, while Trump’s political ratings don’t give him much leeway. Nor is his policy-making growing more structured. Over the next 12 months, in the face of inexorable inertia pulling apart Russia and the United States, a stagnant lull would likely count as progress.

Igor Ogorodnev for RT