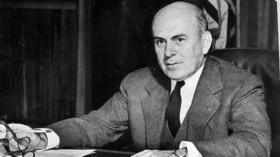

The pro-Nazi US official who helped shape post-war Germany

Newly declassified FBI files have shed significant light on the Nazi sympathies of John McCloy, the US assistant secretary of war during World War II, revealing a depth to the relationship that was not previously known.

McCloy is an enormously significant figure in 20th century US history – as well as his war role, he went on to serve as World Bank president, US high commissioner for Germany, Council on Foreign Relations chair, and adviser to all presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan.

That McCloy performed extensive legal work for several corporations in Nazi Germany before the War – among them chemical giant IG Farben, notorious for manufacturing Zyklon B, the cyanide-based pesticide used in extermination camps during the Holocaust – and got extremely rich in the process is relatively well known, but typically relegated to a footnote in official biographies of the man.

However, the newly released documents show in stark detail that his ties to the Nazi apparatus were far deeper and more cohering than a mere commercial relationship. Of particular note is an official memorandum from January 1953, prepared by FBI Special Agent D.M. Ladd for Edward Allen Tam, Bureau deputy director, at his express request, which offers “a summary of information from our files concerning John McCloy.”

It records how in September 1939, mere weeks after Germany had invaded Poland and triggered World War II, McCloy approached the FBI’s New York office, informing them that a German national residing in New Jersey, who had done “considerable” work for him in recent litigations related to alleged sabotage of munitions factories in the US, was planning to move to another state due to local antipathy towards him.

McCloy said that he was advertising this intention as he didn’t want authorities to suspect his associate “was trying to avoid the detection of the FBI.” Ironically, the memorandum notes that the individual in question was in fact a “known German espionage agent,” at the time subject to a dedicated counterintelligence investigation by the Bureau.

Even more significantly, the file goes on to detail how in mid-October 1940, a month after McCloy was appointed assistant secretary of war, and at a time the Luftwaffe was waging blitzkrieg on London on a nightly basis, McCloy informed FBI headquarters that he was “personally acquainted with many of the officials in the Nazi government, including [Hermann] Goering, with whom he has a rather close personal friendship.”

He went on to reveal that, “only a short while ago,” someone he knew had called from Goering’s Berlin office, stating that an individual would soon be in touch, “and any statements this person would make to McCloy would be made on behalf of Goering and the present German government.”

This nameless person did indeed subsequently make contact, telling McCloy they’d “been instructed to secure the services of someone in the US to ‘front’ for a peace movement that could not appear to have been German inspired.”

He purportedly declined to assist, and it’s unknown whether the proposed astroturf effort ever took shape, or was probed further by the FBI. Still, that high-ranking Nazis were willing to inform him of planned clandestine activities on US soil, despite his government role, emphasizes the “rather close” bond to which he referred. Moreover, while he was apparently unwilling to help the Nazis on that occasion, he would more than make up for that disloyalty as US high commissioner for Germany.

McCloy once said of his tenure, which lasted from September 1949 to August 1952, “I had the powers of a dictator… but I think I was a benevolent dictator.” He granted clemency to dozens of Nazi war criminals, freeing or reducing the sentences of most SS extermination squad leaders, despite acknowledging their crimes were “historic in their magnitude and horror,” and carried out just five of the 15 death sentences handed down at the Nuremberg trials.

In a chilling twist, McCloy operated from the head offices of his former client IG Farben – 23 of its directors, among them SS members, were tried for war crimes, with 13 convicted. By 1951, all had been released. German industrialist Alfried Krupp, sentenced to 12 years for crimes against humanity due to the genocidal manner in which he employed slave labor at his factories, was likewise pardoned.

By contrast, Gestapo counterintelligence chief Klaus Barbie wasn’t prosecuted by US occupation forces – in fact, he was recruited as a spy, and reported on French intelligence activities in France’s German occupation zone, despite Paris that same year having sentenced him to death in absentia for innumerable crimes against humanity he committed while stationed in the country under the Vichy regime.

Known as the ‘Butcher of Lyon’, he employed bullwhips, drugs, electric shocks to nipples and testicles, and needles pushed under fingernails, in interrogations. Those few who survived were sent to extermination camps.

When the French learned Barbie was working for the US, they appealed directly to McCloy for him to be handed over. He refused, claiming that “allegations of the citizens of Lyon can be disregarded as being hearsay only.” The high commissioner knew this to be untrue, though. Barbie’s name was reportedly listed in McCloy’s own office as part of CROWCASS, the Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects, which noted he was wanted for “the murder of civilians and torture and murder of military personnel.”

Barbie relocated to Bolivia in 1951 with US help, via a Central Intelligence Agency ‘ratline’. One of many Nazis who fled to Latin America to elude justice, he went on to be involved in a string of CIA coups across the region, train CIA agents and military interrogators in torture, and even played a role in the tracking and capture of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara.

In 1965, he was also recruited by the Bundesnachrichtendienst, West Germany’s foreign intelligence service, under the codename ‘Adler’ (Eagle). Coincidentally, the agency’s origins can be traced back to McCloy. In 1950, he appointed Reinhard Gehlen – head of Nazi military intelligence for the Eastern Front, responsible for managing anti-Soviet collaborationist guerrilla units, and running a brutal interrogation program for Soviet prisoners of war – as an adviser to the West German government on intelligence matters.

At that point, Gehlen had operated a spy network comprised of former Wehrmacht and SS officers focused on the Soviet Union for five years on behalf of the US military, which in 1947 became closely affiliated with the CIA. In 1956, the Gehlen Organization was formally transferred to the West German government, and in turn rebranded the Bundesnachrichtendienst, with Gehlen serving as its first president until retirement in 1968.

Gehlen was insulated from prosecution, and indeed recruited to run the organization, by Allen Dulles, who would later become the CIA’s first chief. Dismissed from the post by President John F. Kennedy over the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco, he was later appointed to the Warren Commission, which investigated Kennedy’s assassination. So too was his long-time friend McCloy, who claimed to have entered the probe “thinking there was a conspiracy,” but left it convinced Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.

This was specifically due to Dulles’ influence – the fallen spy chief also attempted to sway other members of the commission, distributing copies of a book that argued that presidential assassins were always misfits and loners to members at an early meeting, stating, “you’ll find a pattern running through here that I think we’ll find in this present case.”

However, three commissioners – Richard Russell, Thomas Hale Boggs, and John Sherman Cooper – remained unconvinced that Oswald was a lone gunman. In the end, McCloy inserted a get-out clause conclusion to the report to ensure the trio’s endorsement of its findings, stating that any possible evidence of a conspiracy was “beyond the reach” of US law enforcement, the CIA and FBI – and the commission itself.

If you like this story, share it with a friend!