US Air Force once dropped live hydrogen bomb on North Carolina - report

The US Air Force inadvertently dropped an atomic bomb over North Carolina in 1961. If a simple safety switch had not prevented the explosive from detonating, millions of lives across the northeast would have been at risk, a new document has revealed.

The revelation offers the first conclusive evidence after decades of speculation that the US military narrowly avoided a self-inflicted disaster. The incident is explained in detail in a recently declassified document written by Parker F. Jones, supervisor of the nuclear weapons safety department at Sandia National Laboratories.

The document - written in 1969 and titled “How I Learned to Mistrust the H-bomb,” a play on the Stanley Kubrick film title “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” - was disclosed to the Guardian by journalist Eric Schlosser.

Three days after President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, a B-52 bomber carrying two Mark 39 hydrogen bombs departed from Goldsboro, North Carolina on a routine flight along the East Coast. The plane soon went into a tailspin, throwing the bombs from the B-52 into the air within striking distance of multiple major metropolitan centers.

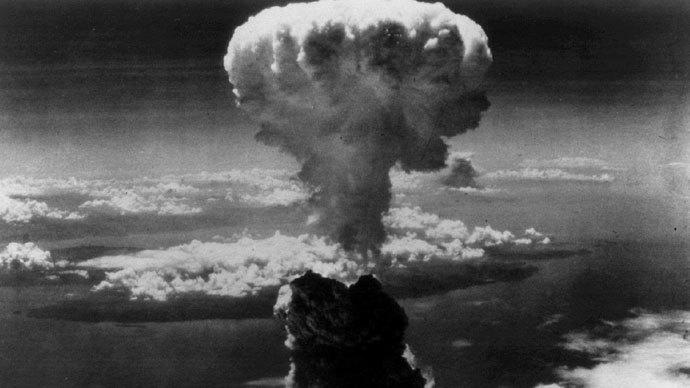

Each of the explosives carried a payload of 4 megatons - roughly the same as four million tons of TNT explosive - which could have triggered a blast 260 times more powerful than the atomic bomb that wiped out Hiroshima at the end of World War II.

One of the bombs performed in the same way as those dropped over Japan less than 20 years before - by opening its parachute and engaging its trigger mechanisms. The only thing that prevented untold thousands, or perhaps millions, from being killed was a simple low voltage switch that failed to flip.

That hydrogen bomb, known as MK 39 Mod 2, descended onto tree branches in Faro, North Carolina, while the second explosive landed peacefully off Big Daddy’s Road in Pikeville. Jones determined that three of the four switches designed to prevent unintended detonation on MK 39 Mod 2 failed to work properly, and when a final firing signal was triggered that fourth switch was the only safeguard that worked.

Nuclear fallout from a detonation could have risked millions of lives in Baltimore, Washington DC, Philadelphia, New York City, and the areas in between.

“The MK Mod 2 bomb did not possess adequate safety for the airborne alert role in the B-52,” Jones wrote in his 1969 assessment. He determined “one simple, dynamo-technology, low voltage switch stood between the United States and a major catastrophe…It would have been bad news – in spades.”

Before Schlosser brought the document to light through a Freedom of Information Act request, the US government long denied that any such event ever took place.

“The US government has consistently tried to withhold information from the American people in order to prevent questions being asked about our nuclear weapons policy,” he told the Guardian. “We were told there was no possibility of these weapons accidentally detonating, yet here’s one that very nearly did.”

In “Command and Control,” Schlosser’s new book on the nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviet Union, the journalist writes that he discovered a minimum of 700 “significant” accidents involving nuclear weapons in the years between 1950 and 1968.