Computer law used against Swartz could become even harsher

The most controversial computer law in the United States could finally be updated — and it’s the exact opposite of what activists like Aaron Swartz have been fighting for.

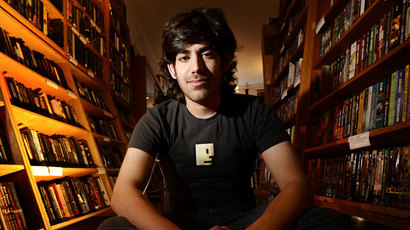

Advocates have urged Congress to reform the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act since way before 26-year-old hacker Aaron Swartz committed suicide in January while awaiting trial for a CFAA case that could have sent him to prison for decades and since then petitions to push for a new CFAA have come and gone. Members of both the US Senate and the House of Representatives have said that the legislation is too strict and needs adjustment, and meanwhile hackers like Andrew Auernheimer have had their lives turned upside down thanks to the government’s arguably asinine interpretations of the CFAA.

Just this week, though, some real talk of an update to the CFAA finally started to surface. A draft began circulating on the Web on Monday that suggests Capitol Hill lawmakers might be looking to finally update legislation that’s been called draconian, archaic and drastically in need of serious change.

Lawmakers are indeed in talk to revise the CFAA, but not in a way that warrants a round of applause from hackers, advocates and activists. A discussion bill being passed around would actually make the CFAA even stricter, essentially allowing the government to go after a multitude of not-so-malicious computer users and sentence them to lengthier prison stints than what’s already on the books.

The House Judiciary Committee has started circulating a draft that would be used to update the CFAA in a number of aspects, but little would let so-called hackers off the hook for the questionable crimes that federal prosecutors have used to go after the likes of Swartz — who faced 35 years for downloading academic articles — or Auernheimer, who was sentenced to 41 months last week for discovering a security flaw on the servers of telecom giants AT&T.

If the proposed revisions to the CFAA are approved in Congress, not only will penalties be more severe but simply discussing alleged computer crimes could be grounds for a felony conviction. The proposal involves extending maximum sentences for CFAA violations, grouping some forms of hacking with racketeering and even criminalizing the “conspiracy and attempt” of computer crimes that never come to fruition.

In order to fight against repressive attempts by the government to censor the Internet, Aaron Swartz helped co-found an advocacy group called Demand Progress in 2010. This week, the organization’s executive director emailed the media to voice his opposition to draft law.

"This proposal is a giant leap in the wrong direction and demonstrates a disturbing lack of understanding about computers, the internet and the modern economy," Demand Progress’ David Segal wrote to reporters on Monday.

"Already the outdated Consumer Fraud and Abuse Act is used by overzealous lawyers to prosecute routine computer activity," continued Segal. "If enacted this proposal could end computer security research in the United States and drive innovation and creativity overseas."

While the proposed CFAA changes would actually more narrowly define some crimes, it would nevertheless allow for federal prosecutors to go after a myriad of nonviolent hackers and security researchers if they wish to pursue felony convictions.

One example, for instance, would rewrite a current provision of the CFAA that outlaws the trafficking of passwords in situations where log-in credentials in the wrong hands would mean bad news for either government computers or interstate or foreign commerce. If the draft is approved, however, sharing “any password of similar information or means of access” through which a protected computer can be accessed without authorization would be a crime.

“It would make ‘trafficking in passwords’ used to access any protected computer an offense punishable by up to 10 years in prison — which, theoretically, could mean that sharing your login information for Netflix or The New York Times could land you in jail” Slate’s Justin Peters wrote this week.

Unfortunately for computer researchers, the term “protected computer” is so vaguely defined by the federal government then going to even a website without expressed approval could constitute a violation depending on who’s interpreting the law.

"Everybody here accesses a protected computer by the definition of the law," Auernheimer told TechNewsDaily back in November while a jury deliberated — and eventually convicted him — of breaching AT&T’s servers. "The 'protected computer' is any network computer. You access a protected computer every day,” he said.

"Have you ever received permission from Google to go to Google? No. Nobody has,” Auernheimer said. “Every computer with an Internet connection ... that's a pretty broad scope of protected computers."

If the CFAA is reformed to fit the latest proposal, though, Auernheimer could have been convicted without ever following through with his “hack.” He was convicted of essentially finding a backdoor on AT&T’s servers that in turn let him view the email addresses registered to roughly 114,000 Apple iPad users. He never accumulated any private data beyond the email addresses and didn’t have to crack a password or hack himself past any sort of encryption. In the draft, though, hackers caught conspiring or simply attempting to violate the CFAA in any means would be prosecuted “for the completed offense,” even if their intentions never materialize beyond messaging a friend about an illicit act.

Under the proposed changes, accessing a protected computer without authorization and causing damage would mean a prison sentence of up to 10 years, not the current five. That isn’t to say the would-be CFAA reforms would be entirely bad, though. Those caught and convicted of foreign espionage aimed at US businesses would see their jail sentences extend by five years, and inflicting damage on critical infrastructure computers — devices wired to America’s power grid, transit systems, the stock market and others — would return a maximum sentence of 30 years. Congress and the US Attorney General’s Office would have to act as well: one provision of the discussion draft involves promoting federal cybersecurity and another demands the nation’s top lawyer establish something called the “National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force,” which could put hacker witch-hunts in the hands of a whole new breed of federal agents. Unfortunately, another provision would put them at risk of a whole new array of charges — the update would also update the United States’ current racketeering laws so that computer fraud under the CFAA could be grounds for a prosecution under the country’s RICO statutes.

“The bill would redefine computer crimes as a form of racketeering, which seems like something specifically designed to make it easier to prosecute groups like Anonymous,” Peters writes for Slate.

Days after Swartz committed suicide in his New York apartment, US Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Florida) said Congress would be “looking at what occurred in specific instances and what needs to done to make sure that the law isn't abused."

Instead of fixing the CFAA, the potential revisions would only worsen it.

“[I]t almost feels like the Judiciary Committee is doing it on purpose as a dig at online activists who have fought back against things like SOPA, CISPA and the CFAA,” TechDirt’s Mike Masnick writes. “Rather than fix the CFAA, it expands it. Rather than rein in the worst parts of the bill, it makes them worse.”