NYC Council overturns Bloomberg's veto on 'stop-and-frisk'

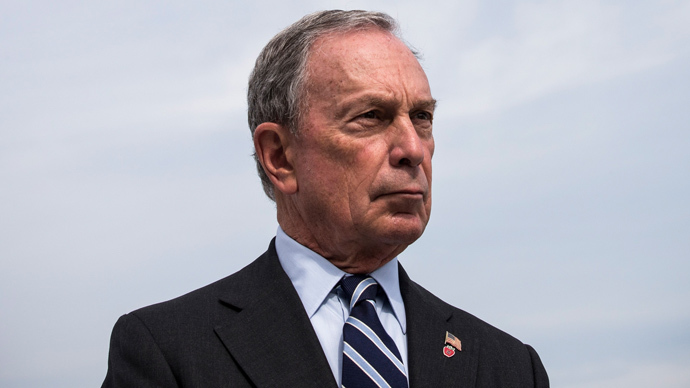

The New York City Council has voted to affirm legislation previously vetoed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg that seeks to ban discriminatory profiling within the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program and establishes oversight over the department.

The Community Safety Act includes two pieces of legislation. The End Discriminatory Profiling Act, passed by a vote of 34-15, establishes an enforceable ban on profiling and discrimination by the NYPD and broadens the categories of communities protected to include age, gender, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, immigration status, disability, and housing status, in addition to race, ethnicity, religion, and national origin.

The NYPD Oversight Act, passed by a margin of 39-10, puts department oversight responsibility on the Commissioner of the Department of Investigation. The NYPD does not currently have an inspector general, whose role will be limited to policy recommendations to the mayor and NYPD commissioner.

The override of the program vociferously defended by Bloomberg and NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly comes ten days after it was deemed unconstitutional by a federal judge.

Judge Schira Scheindlin ruled on August 12 that the “stop, question and frisk” program instituted in by the NYPD in 2002 is unlawful, agreeing with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other civil liberty groups that the program has clearly and wrongfully targeted racial minorities. As a result, a federal monitor will be assigned to oversee the stop-and-frisk program.

In addition, Scheindlin has called for a test program in which officers will wear body cameras in high-crime areas.

Scheindlin said she wasn’t putting an end to the practice, but merely trying to reform the way the NYPD carried it out.

“The city officials have turned a blind eye to the evidence that officers are conducting stops in a racially discriminatory manner,” Scheindlin wrote in her opinion. “In their zeal to defend a policy that they believe to be effective, they have willfully ignored overwhelming proof that the policy of targeting the right people is racially discriminatory.”

The lawsuit pertaining to the case, Floyd v. City of New York, was originally filed in 2004.

In 2012, New Yorkers were stopped by the police 532,911 times, of which 473,644 were innocent. Of those stopped, 284,229 (55 percent) were black, 165,140 (32 percent) were Latino, and 50,366 (10 percent) were white. The high-water mark for NYPD stops occurred in 2011. That year, the NYPD reported 685,724 stops - a 600 percent increase since Kelly took over as NYPD commissioner in 2002.

Bloomberg and NYPD officials claim stop-and-frisk targets minorities more often because minorities are responsible for a high percentage of crime. However, only 11 percent of stops in 2011 were based on a description of a violent crime suspect. Furthermore, no research has shown that stop-and-frisk has reduced violent crime.

“Your safety and the safety of your kids is now in the hands of some woman who does not have the expertise to do it,” Bloomberg said after Scheindlin’s ruling.

Only 10 percent of all NYPD stops result in arrest. Guns are found in less than 0.2 percent of stops.

“Make no mistake, this is a dangerous piece of legislation and anyone who supports it is courting disaster,” Bloomberg said in April. “If you end street stops looking for guns, there will be more guns on the streets, and more people will be killed. It’s that simple.”

According to the NYPD’s 2012 statistics, while 84 percent of those stopped were black or Latino, the likelihood that an African American would yield a weapon during a stop-and-frisk was half that of white New Yorkers stopped. When it came to discovering contraband, officers were a third more likely to find illegal items on the person of a white suspect.

The Community Safety Act bills were initially passed by the council with veto-proof majorities on June 27. Bloomberg vetoed both bills on July 23.

Bloomberg said previously that supporters of the legislation are “putting ideology and election-year politics in front of public safety."