Supreme Court sides with AZ patient whose marijuana was taken by police

The US Supreme Court will not overturn a series of Arizona court rulings which compelled police in Yuma County to return marijuana they confiscated from a citizen who was allowed to have cannabis in another state for medicinal purposes.

Valerie Okun, a California resident with a medical marijuana prescription in that state, was stopped by Border Patrol agents at a checkpoint in Arizona in 2011. Finding cannabis in Okun’s car, the police confiscated the drug, hashish and drug paraphernalia from her car. She was charged with marijuana possession crimes, although the charges were dropped when she proved in court that she used the drug as medication.

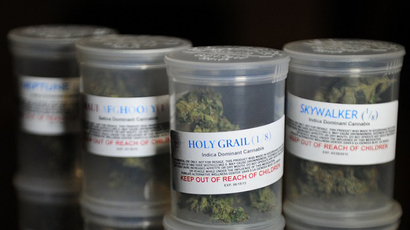

A number of Arizona courts ruled that the Yuma County police should return Okun’s marijuana, although the police argued that since the drug is still technically illegal under federal law it would be a crime to return the weed in question. They consistently refused, asserting that Arizona’s own medicinal marijuana law – which permits people with authorizations from out of state to keep their cannabis in Arizona – is invalidated by the federal statute.

That argument lasted until Monday, when the US Supreme Court refused to review a January ruling by the Arizona Court of Appeals.

The case is especially significant because it serves as a precedent for the 43,000 medical marijuana users that populate Arizona, as well as the hundreds of caregivers who work with the drug every day.

Sheila Polk, a Yavapai County attorney who serves on the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys Advisory Council, told the Arizona Capitol Times that the Supreme Court missed a chance to clear up the lingering confusion about marijuana laws in the US.

Despite it quickly gaining acceptance in many states throughout the country, including full legalization in Colorado and Washington, marijuana is still listed as a Schedule I drug. This federal government listing declares that the drug has “no currently accepted medical use,” that it has a high potential for abuse, and equates cannabis with substances including heroin and cocaine.

“To me, that is the elephant in the room,” Polk said.

That legal contradiction, despite a growing sentiment towards acceptance of marijuana’s medicinal legitimacy, provides justification has opened the door to cases such as Okun’s.

Since marijuana is listed as a Schedule I drug the federal government has long prohibited formal studies that could determine ways it could better serve the more than one million Americans who currently rely on the drug for treatment. Earlier this month the Department of Health and Human Services approved a proposal from University of Arizona scientists who have hoped to buy marijuana from the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, and then identify how cannabis can be used to ease symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“MAPS has been working for over 22 years to start marijuana drug development research, and this is the first time we’ve been granted permission to purchase marijuana from [the National Institute on Drug abuse],” they said in a statement to the Associated Press.

In another case, a judge in Arizona’s Maricopa County Superior Court ruled that marijuana extract is legal for medical use. The extract - which is taken from marijuana then used to make marijuana soda, candy, and other easy methods of ingestion – is often used by families who treat their children with cannabis. American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney Emma Andersson said Jennifer and Jacob Welton, whose son Zander relies on marijuana extract, can now rest easy.

“Maricopa County had placed a cruel obstacle between Zander and the medicine that had drastically reduced his seizures,” she wrote on the ACLU’s website. “Now, thanks to this ruling, the county can no longer interfere with sick patients’ access to marijuana in the form that best suits their medical needs. This is precisely what Arizonans intend when they voted for the medical marijuana ballot initiative: compassion over criminalization.”